Attitudes of patients and doctors towards the use of medical professional terms in Psychiatry

M Aamer Sarfraz, Claire Carstaires, Jinny McDonald, Stanley Tao

Cite this article as: BJMP 2016;9(3):a920

|

|

Abstract Medical professional terms have developed contextually over time for professional communication and patient management. As a part of changes in the National Health Service in the U.K., an interesting trend to change or alter the use of professional terminology without consultation with affected professionals or patients has been noted. This practice is being perceived as a threat to medial professional identity and could be a potential source of inter-professional tensions and poses a risk to patient autonomy and safety. We report findings of a survey among patients and doctors in a psychiatric service to ascertain their attitudes towards some old and new medical professional terms. We found a preference among these important stakeholders for the old medical professional terms and also learned that they have never been consulted about changes in medical professional terminology. Keywords: medical, professional, terminology |

Introduction:

Medical professional terminology is used to communicate with each other, allied professions and differentiates professionals from patients1. As a tradition, it has perhaps evolved into a language of its own with a vocabulary of terms used as expressions, designations or symbols such as ‘Patient’, ‘Ward Round’ and ‘Registrar’. This ‘language’ is not restricted to use by doctors or nurses - it is used among other professionals working in healthcare, e.g. medical coders and medico-legal assistants.

The National Health Service (NHS) in the U.K. has seen many changes in the last few decades. From within these changes, an interesting trend to change or alter the use of professional terminology, often without consultation with directly affected professionals or patients, has emerged. With new or changed roles, multidisciplinary teams have been observed to alter titles, even borrowing specific terms ascribed to doctors such as “consultant,” “practitioner” and “clinical lead”2,3. On the other hand, Modernising Medical Careers initiative4 has also led to changes in doctors’ titles reflecting their experience levels, which have been reported to be unclear to patients and fellow professionals5.

Medical professional terms can be traced back to Hippocratic writings and their development is a fascinating study for language scholars1. Psychiatric terminology is particularly interesting, as it has evolved through scientific convention while absorbing relevant legal, ethical and political trends along the way. Superficially, it may appear pedantic to quibble over terminology, but the power of language and its significance in clinical encounters is vital for high quality clinical care2,6. Since medical professional terminology is an established vehicle for meaningful communication, undue changes in its use can create inaccurate images and misunderstandings, leading to risks for professional identity. There is also evidence to suggest that such wholesale changes have been misleading7 and a source of inter-professional tension.

Understanding of a professional’s qualifications and experience is crucial for patient autonomy and for them to be able to give informed consent. We carried out a survey among foremost stakeholders of medical professional terminology, patients and doctors, within a psychiatric service to ascertain their attitudes to the changes they have experienced in recent years.

Method:

We gave out a self-report questionnaire to all adult psychiatric patients seen at a psychiatric service in the South East (U.K.) in a typical week and to all working psychiatrists/doctors. The questionnaire was developed after a review of the relevant literature and refined following feedback from a pilot project. The questionnaire contained demographic details and questions regarding attitudes towards medical professional terms for patient and professional identity, processes and working environments. The questions were mostly a “single best of four options” style, with one question involving a “yes” or “no” answer.

The datacollected was analysed by using SPSS statistical package8. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of the study population. The two sub-samples (patients & doctors) were compared with each other regarding different variables by using a t-test, which highlighted the absolute and relative differences among those.

Results:

196 subjects were approached to participate. 187 subjects (patients = 92, doctors = 95) participated, which represents a response rate of 95%.

Male to female ratio was roughly equal in the sample but there were more females in the medical group (56%) as compared to the patient (46%) group. Among responders, those over 40 years of age were more prevalent in the patient group (60% vs. 39%) compared to the medical group.

As shown in the Table 1, patients’ and doctors’ attitudes overwhelmingly leaned towards a patient being called a “patient” (as opposed to “client”, “service user” or “customer”); understanding “clinician” as a doctor (as compared to being a nurse, social worker or psychotherapist), and believing psychiatrist to be a “consultant” (preferred to nurse practitioner, psychologist or social worker).

Table1: Patients’ & doctors’ attitudes to medical professional terms = “patient”, “clinician” and “consultant”

| What do you prefer to be called? | ||

| Doctors (%) | Patients (%) | |

| Client | 16 (17) | 13 (14) |

| Patient | 68 (72) | 65 (71) |

| Service user | 10 (11) | 11 (12) |

| Customer | 1 (1) | 3 (3) |

| Don’t know | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 95 | 92 |

| Chi2 1.378, p = 0.710 | ||

| Which of these is a clinician? | ||

| Doctors (%) | Patients (%) | |

| Nurse | 14 (15) | 14 15) |

| Social worker | 4 (4) | 2 (2) |

| Doctor | 56 (59) | 70 (76) |

| Psychotherapist | 7 (7) | 6 (6) |

| Don’t know | 14 (15) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 95 | 92 |

| Chi2 16.3, p<0.05 | ||

| Which of these is a consultant? | ||

| Doctors (%) | Patients (%) | |

| Psychiatrist | 71 (75) | 68 (74) |

| Psychologist | 3 (3) | 6 (7) |

| Social worker | 10 (11) | 10 (11) |

| Nurse practitioner | 3 (3) | 8 (9) |

| Don’t know | 8 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 95 | 92 |

| Chi2 11.3, p<0.05 | ||

Patients and doctors seemed to prefer (>70%) calling the person who provides the patient support in the community as “care-coordinator” or “key worker”.

It is worth noting that “key worker” is the main person looking after the patient admitted to hospital and “care-coordinator” has the same role when they are back in the community. Similarly, the majority of the patients deemed the terms “Acute ward” and “PICU” (psychiatric intensive care unit) appropriate for a psychiatric ward.

There was strong evidence to suggest that both patients and doctors were confused as to what a ‘medication review’ was; as approximately 35% of them thought it was a “nursing handover” and the rest were divided whether it was a “pharmacist meeting” or an “assessment”. See Table 2.

This is understandable because the patients are used to an “Out Patient Appointment/Review” where a psychiatrist reviews patients in a holistic manner, which includes prescribing and adjusting their medications. Similar confusion prevailed regarding what has replaced the term “ward round”, as both groups were universally divided among choices offered as “MDM” (multidisciplinary meeting), “Assessment”, “CPA” (Care Programme Approach) and “Review”.

Table 2: Patients’ & doctors’ attitudes to what a “ward round” and “medication review” means?

| Which of these means a ward round? | ||

| Doctors (%) | Patients (%) | |

| Assessment | 26 (27) | 34 (37) |

| MDM | 18 (19) | 15 (16) |

| Review | 34 (36) | 29 (32) |

| CPA | 16 (17) | 14 (15) |

| Don’t know | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 95 | 92 |

| Chi2 2.82, p = 0.588 | ||

| Which of these is a medication review? | ||

| Doctors (%) | Patients (%) | |

| OPD | 19 (20) | 11 (12) |

| Assessment | 25 (26) | 34 (37) |

| Pharmacist meeting | 34 (36) | 31 (34) |

| Nursing handover | 14 (15) | 12 (13) |

| Don’t know | 3 (3) | 4 (4) |

| Total | 95 | 92 |

| Chi2 3.89, p = 0.421 | ||

Both patients and doctors were clear (84% vs. 69%) that they expected to see a doctor when they attended a “clinic”. However, both groups were approximately equally divided between their preferences for what a psychiatry trainee should be called; “SHO” (37%) or “Psychiatric trainee” (36-40%). There was also a higher preference (approx. 50% vs. 30%) for the doctor a grade below consultant to be called a “Senior Registrar”.

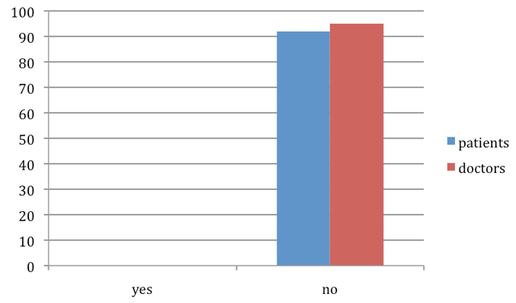

Patients and doctors were equivocal in their response that they have never been consulted about medical professional terminology.

Fig. 1 Has anyone consulted you about these terms?

Discussion:

In a survey of attitudes to the use of medical professional terms among patients and doctors in a psychiatric service, we have found a significant preference for the older and established medical terms as compared to the newer terms such as MDM, CT trainee, Specialty Trainee, etc.

While replicating findings of other studies3,7, we also found that no single term was chosen by 100% of participants in either group, showing confusion surrounding most psychiatric terms. This lack of consensus and confusion can be explained by the fact that no participant had ever been consulted about the changes or new nomenclature.

Limitations to this study should be taken into account before generalising the results. The patients’ group is older than the doctors’ group, which could skew the results due to age related bias in favour of familiarity and against change9. In a questionnaire about preference and understanding, participants may intuitively prefer the easiest to understand terms and ignore the subtle difference between other styles. Possibility of bias may have been introduced by some of those giving out questionnaires being doctors

Our sample was drawn only from a psychiatric service, which may restrict the implications of our findings to mental health.

Furthermore, involvement of other professionals and carers working in the psychiatric service would have been useful to expand the scope of this study.

Inconsistency regarding doctors’ titles, unleashed by the Modernising Medical Careers (2008) initiative, has resulted in patients considering trainees as medical students5, not recognising ‘Foundation Year 1 Trainees’ as qualified doctors and being unable to rank doctors below consultant level3. Our findings have highlighted the uncertainty regarding qualifications and seniority of doctors – this can erode patients’ confidence in their doctors’ abilities, compromise therapeutic relationship10, especially in psychiatry, and result in poor treatment compliance. Medical students may also find themselves mistaken for doctors, and feel daunted by future job progression where training structures and status are unclear.

Title changes introduced by local management or Department of Health (DoH), without consultation with stakeholders, have the potential to create inter-professional tensions and devalue the myriad skills offered by healthcare workers other than doctors. This could also be damaging to their morale and the confidence instilled in patients. It is interesting to note, however, that titles that do not give the impression of status and experience, such as “trainee”, tend not to be adopted by non-doctor members of the multidisciplinary team3. On the other hand, in a profession steeped in tradition, there will be doctors who see other professionals’ adoption of their respect-garnering and previously uncontested titles as a threat to the status of the medical profession6. Previous studies have shown that terminology has a significant effect on the confidence and self-view of doctors5 and at a time where a multitude of issues has led to an efflux of U.K. junior doctors to other countries, and a vote for industrial action, re-examining a seemingly benign issue involving titles and terminology could have a positive impact.

Patients’ attitudes to development of surgical skills by surgical nurses show that they would like to be informed if the person doing a procedure is not a doctor7.

The roles of a number of professionals involved in an individual’s healthcare can be confusing and the possibility of mistaken identity could be considered misleading6, unethical, and even fraudulent. Introducing confusion by appropriating titles associated with doctors could be damaging to patients’ trust, and is inappropriate in a health service increasingly driven towards patient choice. The challenge lies in how to keep the terminology consistent and used in the best-understood contexts.

Commissioners and managers may instead evaluate the implications of changing professional terms by making sure that all stakeholders are consulted beforehand. Perhaps the pressing source of inconsistency in staff job titles could also be rectified by a broader scale study to find national, multidisciplinary and patient preferences, and taking simple measures such as standardising staff name badges.

Our study has highlighted once again how the landscape of nomenclature in psychiatry/medicine is pitted with inconsistency. While language naturally evolves with time and it may be understandable to see increasing application of business models & terminology in the NHS9, medical professional terms have been determined contextually over the years with significant implications for patient management and safety. Therefore, it is important to question how changes in terminology affect patients, whether it occurs by gradual culture change or due to new initiatives. It would benefit patient care if medical and psychiatric professional language could be standardised and protected from changes, which can lead to colleagues and patients being misled. DoH, Commissioners and Trust/Hospital management must recognise that changing terminology can have a significant impact and that serious discussion of such changes is important for reasons far beyond pedantry. For inter-professional communication a formalised consensus on titles would be beneficial for transparency, trust, patient safety and reducing staff stress levels.

|

Competing Interests None declared Author Details M AAMER SARFRAZ, Consultant Psychiatrist & Director of Medical Education, Elizabeth Raybould Centre, Bow Arrow Lane, Dartford DA2 6PB, UK. CLAIRE CARSTAIRS, KMPT, Dartford, Kent, U.K. JINNY MCDONALD, KMPT, Dartford, Kent, U.K. STANLEY TAO, East Kent Hospitals, Canterbury, U.K. CORRESPONDENCE: DR M AAMER SARFRAZ, Consultant Psychiatrist & Director of Medical Education, Elizabeth Raybould Centre, Bow Arrow Lane, Dartford DA2 6PB, UK. Email: masarfraz@aol.com |

References

- Freidson E. Profession of Medicine: A Study of the Sociology of Applied Knowledge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1970.

- Thalitaya MD, Prasher VP, Khan F, Boer H. What's in a name? - The Psychiatric Identity Conundrum. Psychiatr Danub. 2011 Sep; 23 Suppl. 1:S178-81.

- Hickerton BC, Fitzgerald DJ, Perry E, De Bolla AR. The interpretability of doctor identification badges in UK hospitals: a survey of nurses and patients. BMJ Qual Saf2014;23:543-547 doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002445

- Delamonthe T. Modernising Medical Careers: final report. BMJ. 2008 Jan 12; 336(7635): 54–55)

- Van Niekerk J, Craddock N. What’s in a name? BMJ Careers 4th May 2011.

- Proehl J, Hoyt KS. Evidence versus standard versus best practice: Show me the data! Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal. 2012; 34(1), 1–2.

- Cheang PP, Weller M, Hollis LJ. What is in a name—patients’ view of the involvement of ‘care practitioners’ in their operations. Surgeon. 2009; 7:340–4.

- Argyrous, G. Statistics for Research: With a Guide to SPSS. London: SAGE. ISBN 1-4129-1948-7.

- Sharma, V, Whitney, D, Kazarian SS, Manchanda R. Preferred Terms for Users of Mental Health Services Among Service Providers and Recipients, Psychiatr Serv. 2000; 51:677.

- McGuire R, McCabe R, Priebe S. Theoretical frameworks for investigating and understanding the therapeutic relationship in psychiatry. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2001; 36: 557–564.

- World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/text.jsp?file_id=283854.American Medical Association Advocacy Resource Centre ‘Truth in Advertising’. 2008. Available from:http://www-ama.assn.org/resources/doc/arc/x-ama/truth-in-advertisingcampaign.booklet.pdf

The above article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.