A comparative review of admissions to an Intellectual Disability Inpatient Service over a 10-year period

Cristal Oxley, Shivanthi Sathanandan, Dina Gazizova, Brian Fitzgerald, Professor Basant K. Puri

Cite this article as: BJMP 2013;6(2):a611

|

|

Abstract Aim: To analyse trends in admissions to an intellectual disability unit over a ten year period. |

INTRODUCTION:

People with intellectual disabilities are a heterogeneous group, who can pose a challenge to services in terms of meeting a wide range of needs. Following the closure of large institutions, the optimum means of service provision for people with intellectual disabilities with additional mental illness and challenging behaviour has been a matter of debate.

Challenging behaviour can be defined as a ‘culturally abnormal behaviour of such an intensity, frequency or duration that the physical safety of the person or others is likely to be placed in serious jeopardy, or behaviour which is likely to seriously limit use of, or result in the person being denied access to, ordinary community facilities’ – Emerson, 19951. Examples of challenging behaviours include self-injury, aggressive outbursts, destruction of property and socially inappropriate behaviour.

The credit-crunch of recent years has led to an increased use of private sector services delivering care to NHS funded patients. The Winterbourne Scandal unearthed by BBC Panorama in June 2011 (an investigation into the physical abuse and psychological abuse suffered by people with learning disabilities and challenging behaviour at this private hospital in South Gloucestershire), highlighted that whist this maybe an economically viable option, fundamental questions were raised about whether private sector services’ safeguards and monitoring protocols were as robust as the NHS in protecting vulnerable patients. It also reawakened longstanding disputes around the way people with complex needs are cared for in residential settings. The discussions centred around ‘institutional’ versus ‘community’ care styles; specialist intellectual disabilities services versus generic adult psychiatric services; local versus specialist expertise congregated around a single unit; and also financial questions regarding how best to meet the needs of this population at a time of austerity. Opinions vary widely, and at times are even polarised, as a result of several factors including position within this competitive and complex system, personal and cultural politics and also personal experience. As a result of the government review, subsequent to the Winterbourne investigation, a number of recommendations have been made which will affect the future of care of this vulnerable group of patients. These include, “by June 2013, all current placements will be reviewed, everyone in hospital inappropriately will move to community-based support as quickly as possible, and no later than June 2014… as a consequence, there will be a dramatic reduction in hospital placements for this group of people”2

The Department of Health Policy, Valuing People3, set out ‘ambitious and challenging programme of action for improving services’, based on four important key principles – civil rights, independence, choice and inclusion. Government Policy as detailed in both Valuing People and the Mansell Report3, 4 recognises that NHS specialist inpatient services are indeed necessary on a short-term basis for some people with intellectual disabilities and complex mental health needs. Inpatient facilities for people with Intellectual Disability have been described as highly specialised services that are a valuable, but also expensive, component of mental health services5. The Enfield Specialist Inpatient unit - the Seacole Centre - is one such service.

The Seacole Centre consists of two inpatient units, with a total of 12 inpatient beds, for people with intellectual disabilities with acute mental illness and/or challenging behaviour. It is located within Chase Farm Hospital in Enfield, Greater London. The Seacole Centre has a multidisciplinary team consisting of nurses, psychologists, psychiatrists, a resident GP, occupational therapists, intensive support team staff, physiotherapists, speech and language therapists, a physical exercise coach and administrative staff. Patients are admitted from a variety of sources, including general psychiatric wards, general medical wards and community intellectual disability teams. Since patients are often referred from other boroughs, in addition to this multidisciplinary team, each patient has their own community and social care team based within their own borough. The use of out-of-area units faces similar challenges to out-of-area placements, use of which has been increasing in the UK, and it is important to explore ways in which service users, out-of-area, can be supported effectively6.

In 2002, a review of admissions to the unit was completed to describe the management of mental illness and challenging behaviour. Since then there have been several service reconfigurations within the trust, in order to accommodate national, political and financial recommendations. However, despite these changes, it was observed clinically that certain clinical problems including delayed discharges continue to occur. We decided to complete a similar review, to describe current admission trends in further detail, in order to enable us to identify areas of improvement, and also to ascertain the nature and severity of ongoing problems to focus future recommendations.

METHOD:

A retrospective review of the case records of all inpatient admissions to the Seacole Centre was completed over a three-year period – from 1st January 1999 to 31st December 2001.

Data collected included age on admission, gender, borough, diagnosis, psychotropic medication on discharge, date of admission and discharge, length of stay, legal status on admission, delays on discharge, and reason for delay, and living arrangements prior to and after discharge

A successful outcome of admission was discharge from hospital to community care. We used the following definition of the delayed discharge:

"A delayed transfer occurs when a patient is ready for transfer from a general and acute hospital bed but is still occupying such a bed. A patient is ready for transfer when:

- a clinical decision has been made that the patient is ready for transfer

- a multi-disciplinary team decision has been made that the patient is ready for transfer

- the patient is safe to discharge/transfer.7

The review was repeated during a further three-year period between 1st January to 2009 and 31st December 2011.

RESULTS:

Characteristics of 1999-2001 cohort, and comparison with 2009-2011

The basic demographic details can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1 - Demographic details

| 1999-2001 | 2009-2011 | |

| Number of admissions | 60 | 41 |

| Number of patients | 46 | 40 |

| Average (mean) age/years | 29.58 | 36.16 |

| Age Range / years | 14-63 | 19-72 |

| M:F ratio | 1.4:1 | 3.1:1 |

| Total number of boroughs from which patients admitted | 10 | 7 |

Trends in Admission Rates

As seen in Tables 1 and 2, there has been a reduction in the total number of admissions between the studies. There has also been a marked reduction in re-admissions. The average length of stay has increased, and although the number of delayed discharges has slightly decreased, it can be seen that this is still a factor in a significant proportion of the admissions.

Table 2 - Trends in admission

| 1999-2001 | 2009-2011 | |

| Total Number of admissions | 60 | 41 |

| Average (mean) length of stay / days | 198.6 | 244.6 |

| Number of readmissions | 16 | 1 |

| Number of delayed discharges | 40 (67%) | 24 (59%) |

Reason for admission

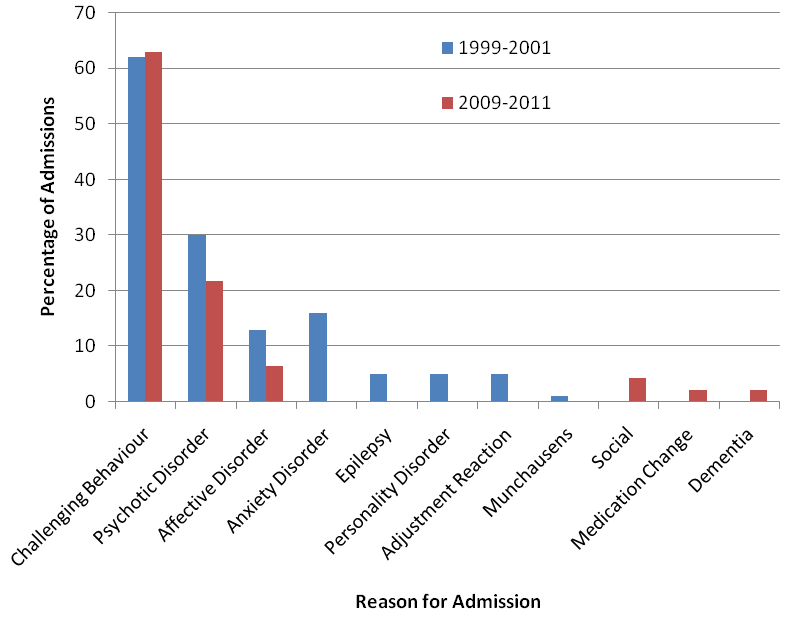

The trends in reason for admission are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Trends in Reason for Admission, 1999-2001 compared to 2009-2011

In both time periods, the most frequent reason for admission is challenging behaviour (62%, n=37 between 1999-2001; 63%, n=29, between 2009-2011), followed by psychosis (22%, n=13 between 1999-2001; 11%, n=5, between 2009-2011. Social admissions were the third most common reason for admission in the recent study (0% between 1999-2001; 4%, n=2 between 2009-2011). The range of psychiatric presentations was widest during the original time period.

Patterns on discharge

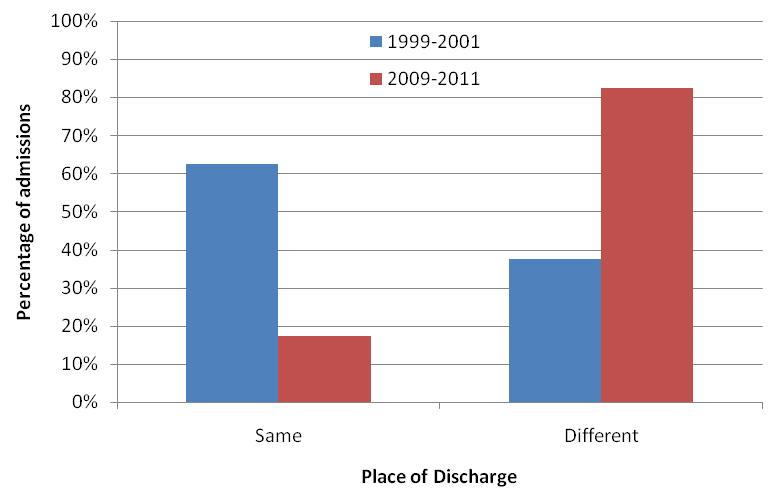

As shown in Figure 2, most patients in the original study were discharged to either the same residential home or back to the family home, where as in the latter time period patients were most frequently discharged to either a different residential home or to supported living. Figure 3 summarises this effect, demonstrating the change in discharging the majority of patients to a different place of residence.

Figure 2 – A graph to show the place of discharge, 1999-2001 compared to 2009-2011

Figure 3 – A Graph to Demonstrate Trends in Place of Discharge – comparing 1999-2001 and 2009-2011

Delayed discharges

The primary cause for delay in both studies was finding appropriate placement, although this was more marked in the recent cohort.

One of the major factors contributing to delayed discharges was lack of identification of suitable placement, which was identified as a major contributing factor to delayed discharges in 69% of cases in 2009-2011 and in 44% in 1999-2001, and apparent delays in the role played by social services (table 2).

DISCUSSION:

Throughout this study spanning 10 years, challenging behaviour followed by psychotic disorder remained the most common cause for admission. Interestingly, by 2008-2011, the third most common cause for admission was related to social reasons (4%). There were no admissions in the original study for this reason. Between 1999 and 2001, there were a wider range of reasons for admission across the mental illness spectrum compared to 10 years on. In previous studies, the largest diagnostic group for all admissions was schizophrenia spectrum disorders7,8. However, between 2009-2011, more than a quarter of patients admitted to the Seacole Centre did not have any psychiatric diagnosis on admission. It is important to keep in mind that individuals with intellectual disabilities accessing specialist inpatient services are more likely to present with complex clusters of symptoms and behavioural problems that may span several diagnostic categories.

The most significant improvement from the original review and the re-review is that the number of re-admissions significantly reduced from 24% (14 patients) to 2% (1 patient). Of interest to note is that during 1999-2001 a large proportion of patients were discharged to their original place of accommodation (often the family home) whereas in 2009-2011, it was more common for patients to be discharged to a new place of living, more suited to managing increasing complex needs and behaviours. This may account for some of the reduction in re-admission rates.

The length of stay over the 10-year period has slightly increased from an average of 198.6 days up to 244.6 days, which demonstrate that admissions are considerably longer than in more generic medical settings. The findings are in keeping with a number of other studies regarding patients with intellectual disability who are admitted to a specialist unit and continue as inpatients for significantly longer periods. One study showed a mean length of stay 23.2 weeks for a specialist unit versus 11.1 weeks in generic settings 8. Another study in South London revealed similar finds of 19.3 weeks compared with generic unit stays of 5.5. weeks9. An exploratory national survey of intellectual disability inpatient services in England has shown that 25% of residents had been in the units for more than two years. Only 40% of residents had a discharge plan, and only 20% had both this and the type of placement considered ideal for them in their home area10. Reasons for length of stay are not fully understood in any of these studies. They may include fear of taking risks, lack of local safe or competent amenities, lack of experience or authority amongst those charged with sourcing bespoke services for complex people with challenging needs, and also a potential lack of such resource in terms of time available to see people, read reports, meet with stake holders and find the right services. The results of another retrospective study comparing the generic and specialist models in two districts in the UK by Alexander et al11 suggested that, within the same district, patients do stay longer in the specialist unit, but they are less likely to be discharged to an out of area placement.

There is no evidence to suggest that comprehensive care for people with intellectual disabilities can be provided by community services alone. Likewise, there is also no clear evidence to suggest that a balanced system of mental health care can be provided without acute beds12. There is, however, clear evidence that services created by the private sector are used very widely and seen as at time as an economically viable option in the current climate of credit crunches.

The different models of inpatient service provision that have been suggested range from mainstream adult mental health services; alternatively an integrated inpatient scheme whereby people with Intellectual disabilities with additional mental illness or severe challenging behaviour are admitted to adult mental health beds, with provision for extra support from a multidisciplinary learning disabilities team; ranging across to specialist assessment and treatment units13,14.

Inpatient care is known to consume most of the mental health budget15 and specialist inpatient units are an expensive component of these services. Cost containment and cost minimisation of inpatient beds within the current economic recession presents a real challenge for those charged with responsibility to provide high-quality, effective, specialist care for adults with intellectual disability. Such cost reduction could be approached in a number of ways, through the reduction of length of stay, optimising drug budgets, reducing rates of re-admissions, and establishment of projects in association with the voluntary and statutory sector to facilitate prompt and safe discharge.

Reducing the average length of stay where possible can reduce the cost, and the resources and budget freed up in this way could be used for other service components15. However, this single agenda can lead to problems of pressured early discharge to unsuitable placements. It is known that resource consumption is most intense during the early stages of admission. As such, we observe a position whereby reducing length of stay requires proactive planning throughout the whole process of care, as well as active discharge planning, with a need for clearly defined pathways of care.

A crucial aspect of the patient's transition through inpatient placement to life in the community is efficient and regular communication between the relevant professionals and teams who form part of continuity of on-going care back in the community. This can at times be particularly challenging owing to differences in values and perceptions about patient need and problem, and also varying pressures. Understanding and resolving problems for individuals with complex and severe challenging behaviour or mental illness that requires a period of containment in a specialist service also requires specialist on-going work and risk management to ensure that when the problems are contained and understood, they remain contained and understood on discharge and thereafter so long as the individual remains vulnerable to the point of requiring any care giving. Many people from the general population who develop a serious mental illness requiring hospitalisation, have capacity once well, to make decisions for themselves and articulate a need or otherwise for specific care or intervention. This is rarely completely the case for people with Intellectual disabilities. Collaborative approaches together with those involved in community care is crucial to getting the right care at the right financial cost for this relatively small but very complex and vulnerable group of individuals.

|

Competing Interests None Author Details Cristal Oxley, Core Psychiatry Trainee 3, Central & North West London NHS Foundation Trust. Shivanthi Sathanandan, Core Psychiatry Trainee 3, Central & North West London NHS Foundation Trust. Dina Gazizova, Consultant Psychiatrist in Intellectual Disabilities, Central & North West London NHS Foundation Trust. Brian Fitzgerald, Consultant Psychiatrist in Intellectual Disabilities, Central & North West London NHS Foundation Trust. Professor Basant K. Puri, Honorary Clinical Research Fellow (Department of Medicine), Hammersmith Hospital and Imperial College London. Department: The Seacole Centre, Enfield Learning Disabilities Service, Chase Farm Hospital, The Ridgeway, Enfield, EN2 8JL. CORRESPONDENCE: Cristal Oxley, Core Psychiatry Trainee 3, Central & North West London NHS Foundation Trust. Email: cristaloxley@nhs.net |

References

- Emerson, E. (1995) Challenging Behaviour. Analysis and Intervention in Peopls with Learning Difficulties. Cambridge University Press.

- DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH website - “Government publishes final report on Winterbourne View Hospital” http://www.dh.gov.uk/health/2012/12/final-winterbourne/

- DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH (2001) Valuing People. A New Strategy for Learning Disability in the 21st Century. CM 5086.TSO (The Stationery Office).

- Department of Health Services for people with learning disability and challenging behaviour or mental health needs (Mansell report, revised edition). 2007, London, The Stationary Office, Department of Health.

- Hassiotis A., Jones L., Parkes C., Fitzgerald B., Kuipers J. & Romeo R. Services for People with Learning Disabilities and Challenging Behaviour from the North Central London Strategic Health Authority Area: Full Report of the Findings from the Scoping Project. North Central London Strategic Health Authority, 2006 London.

- Barron D, Hassiotis A, Paschos D. Out-of-area provision for adults with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviour in England: policy persepectives and clinical reality. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2011, Sep:55(9): 832-43

- C. P. Hemmings, J. O’Hara, J. McCarthy, G. Holt, F. Eoster, H. Costello, R. Hammond, K. Xenitidis and N. Bouras, Comparison of adults with intellectual disabilities and mental health problems admitted to specialist and generic inpatient units. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 2009, 37: 123–128

- Xenitidis K., Gratsa A., Bouras N., Hammond R., Ditchfield H., Holt G.Psychiatric inpatient care for adults with intellectual disabilities: generic or specialist units? Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 2004, 48:11–8.

- Saeed H., Ouellette-Kuntz H., Stuart H. & Burge P. Length of stay for psychiatric inpatient services: a comparison of admissions of people with and without developmental disabilities. J Behav Health Serv Res, 2003, 30: 406–17

- Mackenzie-Davies N & J. Mansell. Assessment and treatment units for people with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviour in England: an exploratory survey Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 2007, 51 (10): 802–811

- Alexander R. T., Piachaud J. & Singh I. Two districts, two models: in-patient care in the psychiatry of learning disability. British Journal of Developmental Disabilities 2001, 93: 105-10.

- Thornicroft, G. & Tansella, M. Balancing community-based and hospital-based mental health care. World Psychiatry, 2002, 1: 84-90.

- Singh I, Khalid MI, Dickinson MJ . Psychiatric admission services for people with learning disability. Psychiatr Bull 1994;18:151–152

- Hall I., Higgins A., Parkes C., Hassiotis A. & Samuels S. The development of a new integrated mental health service for people with learning disabilities. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 2006,43: 82–87.

- Knapp, M., Chisholm, D., Astin, J., et al The cost consequences of changing the hospital – community balance: the mental health residential care study. Psychological Medicine, 1997,27: 681 -692

- Bouras N, Holt G Mental health services for adults with learning Disabilities, British Journal of Psychiatry, 2004, 184:291-292.

The above article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.