Using Mentoring To Improve the Foundation Placement in Psychiatry: Review of Literature And A Practical Example

Yasir Hameed, Hugo deWaal, Emma Bosier, James Miller, Jane Still, Dawn Collins, Thomas Bennet, Clara Haroulis, Jacobus Hamelijnck & Nigel Gill

Cite this article as: BJMP 2016;9(4):a932

|

|

Abstract In the past few years, mentoring in clinical settings has attracted the attention of medical educators, clinicians, managers, and policy makers. Most of the Royal Colleges of medical and surgical specialities have some form of mentoring schemes and various regional divisions of Health Education England support mentoring and coaching in the workplace. Despite the importance of this topic and the great need to provide more support to doctors in recent times, there is a paucity of literature on examples of mentoring schemes in clinical settings and practicalities of setting up such schemes in hospitals. This paper describes the implementation of a mentoring scheme in a large mental health trust in the UK to support junior doctors and the issues involved in creating such scheme. We hope that this article will be useful to clinicians who would like to start similar schemes in their workplace. Keywords: Mentoring, Clinical, Education envionemnt, Best evidence medical education. |

Introduction

In the UK, all newly graduated doctors spend their first two years of work rotating between different specialities, usually spending four months in each placement, before applying for speciality training. This period is called the Foundation Programme.

In January 2016, the Royal College of Psychiatrists published its first ever strategy on Broadening the Foundation Programme to address the need to improve the psychiatric training experience for foundation doctors. The strategy’s aim is to “ensure the delivery of a high-quality training experience in all psychiatry foundation placements”.1

Over the last few years, the number of Foundation training posts in psychiatry in England and Wales has significantly increased. Health Education England aims that all Foundation doctors should rotate through a community or an integrated placement (psychiatry is considered as a community placement) from August 2017.2

As such, the College highlights the need to provide a supervised and well-structured psychiatric training experience for Foundation doctors. This aims not only to improve recruitment into psychiatry but also to ensure doctors have a good working knowledge and understanding of psychiatry and psychiatric services, no matter what career they pursue.

Mentoring provides an additional support and therefore can be helpful to improve the placement of Foundation doctors in psychiatry.

We implemented an ambitious mentoring scheme in Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust (the seventh largest mental health trust in the UK). The paper describes its essential component together with a brief review of the literature on mentoring in clinical settings, focusing on Foundation placements.

Why is mentoring is needed for Foundation doctors in psychiatry?

The literature on mentoring for medical professionals draws attention to the idea that it is beneficial to all doctors at all stages of their career to experience mentoring in some form or another. However, mentoring is of particular importance to doctors moving to a new job or organisation 3, thus making it highly relevant to Foundation trainees.

For newcomers, most of the mentoring support will focus on helping them settle into their new role, becoming familiar with, and developing an understanding of the expectations of their employers.4

Evidence shows that the quality of care in any organisation can be improved when clinical leaders support time for activities such as reflection, coaching and mentoring 5.

Most Foundation doctors will lack experience in psychiatry and will need a substantial amount of guidance from their supervisors and their teams.6 Research has shown that the transition from student to doctor is a difficult one and can be associated with significant levels of emotional stress.7

Foundation doctors find psychiatric assessments physically and emotionally challenging. They feel they lack the specialist knowledge and skills to deal with complex patients, especially concerning self-harm, personality and eating disorders. Dealing with such complex diagnostic categories requires knowledge, skill, understanding as well as physical and emotional robustness. Due to the relative lack of focus on such topics in most undergraduate medical training, a comprehensive support in psychiatric placements is essential.

Psychiatry is very different from other specialities in the way services are configured and delivered: junior doctors may face isolation as psychiatric units are typically spread across a wide geographical area and often lack a centralised meeting place for junior doctors (e.g. a doctors’ mess). In addition, they may find themselves the lone practitioner when on call, which can be daunting for many.

Clinical and Educational supervision is provided to Foundation doctors in similar ways to other rotations. However, the consultants delivering this essential support often focus only on clinical issues related to knowledge and skills. Furthermore, it is easy to see that the best guides to new trainees regarding the idiosyncrasies of the speciality and its services are likely to be trainees who have spent some time in those services and are more able to detect the specific stresses new doctors may experience and may find difficult to articulate.

Furthermore, mentoring fosters a productive peer-to-peer relationship. The learning needs of the Foundation doctor can be considered alongside their personal and professional interests and lifestyle. Questions can be posed in a non-judgmental forum, without fear of being ridiculed or condemned. The fundamentals of on-call systems, clinical cases and management options can all be considered at a level appropriate to their junior grade. Tips for examination success and information about essential courses and core texts can be shared. Job choices and research opportunities can be discussed. Day to day difficulties and mismatches between expectation and reality can be identified and possibly overcome. Where this is not possible next steps can be identified, and clinical and educational supervisors can be drawn in for higher level support. The benefits of the scheme are broad.

Finally, although mentoring is different from role-modelling (teaching by example and learning by imitation), it has been shown toserve some of the same aims of role-modelling, including enhancing problem-solving abilities of the mentee, improving professional attitudes, showing responsibility and integrity, and supporting career development. 8

What is mentoring?

Mentoring can mean different things to different people. There are various definitions which can create confusion between mentoring and other formal structures of support such as supervision, coaching, consultation, befriending or friend systems and even counselling. However, mentoring is none of the above but at the same time a combination of them.

The Standing Committee on Postgraduate Medical and Dental Education (UK) defined mentoring as ‘The process whereby an experienced, highly regarded, empathetic individual (the mentor) guides another individual (the mentee) in the development and re-examination of their ideas, learning, and personal and professional development”.9

The term “mentoring” takes us back to Greek mythology: Mentor was a person: he was the friend of Odysseus who was asked to look after Odysseus’ son Telemachus when Odysseus was fighting in the Trojan Wars. The name Mentor was later used to describe a trusted person, a supporter, or a counsellor.10

Mentoring as a professional developmental tool became popular in the private sector organisations in the USA during the 1970s and was introduced to the area of health during the 1990s 11. Since then, it has been widely used in various organisations.

Aims of mentoring

Mentoring has the advantage of being a flexible supporting tool, unlike other structured processes (e.g., clinical supervision or coaching) where the goals are set clearly from the start of the relationship between the supervisor and supervisee. The aims of mentorship are summarised in Table 1.

| Table 1- Aims of mentorship |

|

Types of mentoring

Buddeberg-Fischer and Herta 11 discussed various types of mentoring based on the numbers of mentors and mentees and their professional status or grade:

- One to one mentoring (between a mentor and a mentee).

- Group mentoring (one mentor and a small group of mentees)

- Multiple-mentor experience model (more than one mentor assigned to a group of mentees).

- Peer-mentoring (the mentor and mentee are equal in experience and grade): This mentoring is used mainly for personal development and improving interpersonal relationships. Mentor and mentee roles can be reversed. Also, called ‘co-mentoring’.

Distance or e-mentoring is becoming more popular, and it has the advantages of being “fast, focused, and typically centred on developmental needs”. 12

Structured vs. flexible mentoring

Evidence suggests that providing mentorship through a rigid and structured process can be counterproductive. 13 Mentors and mentees usually work in different locations, making it difficult for both to have a set of pre-planned meetings and topics for discussions.

Another advantage of the flexibility of mentoring is that it does not follow a “tick box” exercise but encourages informal discussions and exploration of whatever comes to mind during meetings. Doubtless, having some structure to the overall mentoring process is important as it ensures that the mentoring session doesn’t become an informal befriending or friend support system. Table 2 sets out the main benefits of mentoring.

| Benefits to the organisations | Benefits to the mentee | Benefits to the mentor |

|

|

|

Table 2-Benefits of mentoring. Developed from Mentoring – Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) Factsheet. Revised February 2009 14. Available from: https://www.shef.ac.uk/polopoly_fs/1.110468!/file/cipd_mentoring_factsheet.pdf

Are there any Disadvantages of mentoring?

There is extensive literature on the benefits of mentoring, but is there any harm associated with it?

As with any intervention, it does carry some potentially adverse effects. Mentoring can be perceived to “infantilise” junior employees rather than empowering them 10. This perception is probably more common among employees who see themselves as senior or very competent and think of themselves as able to adapt to change very quickly.

Mentoring might hinder creativity in new employees and inhibit them from thinking “outside the box” as it might re-enforce the message that ‘this is how we do things here’. 10

Clashes of personalities or other interpersonal factors could lead to a troubled mentor-mentee relationship and cause distress to both parties. Hence, plans must be put in place in any formal mentoring scheme to ensure an amicable ending to this relationship. Multiple mentor allocation mentioned earlier could also prevent such interpersonal problems and help to tackle them early on.

Furthermore, some mentees may feel uncomfortable with the influence or authority of the mentor, and this may hinder the progress of the mentoring relationship. 13 This is particularly relevant when the mentor is also involved in the formal assessment of the performance of the mentee (e.g. being the line manager or supervisor) or when a mentee who lacks self-confidence is paired with an overconfident mentor.

Good mentors avoid common pitfalls in the mentoring process, such as a patronising attitude, breaches of confidentiality and offering direct advice to the mentees. Instead, they encourage the mentee to reflect and come up with their answers. 15

Finally, mentoring can be perceived as an additional demand on doctors during their training, and some may feel that they are forced to provide it or receive it during placement. However, it must be remembered that mentoring should always be voluntary and flexible to meet the individual’s needs and not an additional ‘box to tick’ or a portfolio enrichment exercise.

The Mentoring Scheme for Foundation Doctors in Psychiatry Norfolk:

The scheme started in December 2015 and initially ran as a pilot in Norfolk with the support of all stakeholders. The mentoring scheme coordinator (YH) contacted twelve Foundation doctors by email, welcoming them to the Trust and inviting them to participate. The welcome email contained information about mentoring, including the benefits it may offer.

The voluntary nature of this scheme was highlighted so that the doctors didn’t feel they were being pressured to be enrolled.

Of the 12 doctors invited, five took up this opportunity. Uptake has remained constant over the consequent cohorts of Foundation doctors for many reasons. Those deciding not to enrol in this scheme explained that they felt happy with the support provided by their clinical supervisors. However, some doctors asked for a mentor halfway through their placement when they felt that they needed additional support. In these instances, a mentor was allocated to them as soon as possible.

Mentors were core and higher trainees already involved in supporting more junior psychiatric trainees through informal mentoring. Their experience meant there was no need for formal training. However, reading material was circulated to them to highlight the roles and responsibilities of mentors and what to do if any problem arose during mentoring. Monthly mentors’ meetings were very helpful to discuss issues arising in mentoring and offer peer to peer support.

Also, there were regular meetings and discussions between the mentoring coordinator, the Director of Medical Education, and Medical Director of the Trust to resolve any issues facing the Foundation doctors and provide feedback to improve the Psychiatric placement.

During the first meeting, the mentors and mentees agreed on the aims of mentoring drawing up a list of objectives that the Foundation doctor would like to achieve by the end of the placement. Following this initial meeting, there should have been once monthly face to face meetings throughout the placement. The mentor and mentee agreed on the most convenient means of communication (e.g. using text messages, emails, etc.) outside scheduled meetings.

All mentors kept a record of the mentoring meetings, with the mentoring coordinator informed about these meetings. Issues discussed were confidential and not shared with the coordinator or supervisors unless the mentee gave specific consent.

At the end of the mentoring scheme, the coordinator collected feedback from mentees and mentors using a structured questionnaire that was designed by the coordinator using SurveyMonkey® website. The feedback highlighted the positive aspects of mentoring as well as areas for improvement.

End of mentoring survey

Mentors reported that acting as a mentor without being involved in clinical supervision allowed them to offer objective advice and support in a way that would have been harder if they were directly involved in the workplace. One Foundation doctor experienced bullying from another member of the team who was a locum doctor. The mentor supported the Foundation doctor, and the issue was addressed and resolved promptly. There was a significant risk that they would have been left isolated and unsupported during this time if the mentor scheme had not been in place.

The topics discussed were varied, and this suggested that mentoring was not limited to a aspect of the job (see Table 3)

| Table 3- Topics discussed in mentoring meetings |

|

Mentees reported that they found mentoring useful and supportive of learning and development. This was especially important in a speciality that they had little experience of as an undergraduate. With a mentor in Psychiatry, the Foundation doctors reported that they could identify areas of development, including leadership and teaching opportunities for Foundation doctors.

Overall, mentoring was shown to be a useful tool to improving Foundation doctors’ experience in Psychiatry by offering extra support during placement in a challenging medical speciality.

Table 4 summarises the areas of development suggested by the mentors and mentees.

| Table 4- Recommendations from the feedback of mentors and mentees |

|

Limitations

Feedback from mentors and mentees showed an overall satisfaction with the scheme, but it was not possible to measure such satisfaction quantitatively, this was expected from an approach which is willfully kept outside the realm of performance management.

According to the literature on mentoring, most mentoring schemes lack a clear structure, as well as a clear evaluation process of its short and long terms, benefits 11.In our scheme, we addressed this by continually monitoring the mentoring process and collecting feedback from mentees and mentors. Another limitation involves training the mentor himself and finding the time in a highly pressurised and heavy workload environment.

There are many questions that the literature on mentoring is yet to answer. For example, what are the long-term benefits of mentoring? Would our Foundation doctors who received mentoring be more successful professionally and personally compared to their peers who decided not to participate? These questions remain unanswered as our pilot was not set up to address this general shortcoming of current knowledge and understanding.

Conclusions and recommendations

Mentoring provides a focused opportunity to target the wider needs of the trainee. Not only could this encourage Foundation doctors to pursue a career in Psychiatry, but it also provides the space for them to learn how to incorporate psychiatric skills into whatever speciality they choose to pursue.

As a new doctor in a novel environment, being expected, welcomed, and gently guided into the job is invaluable. With the hindsight of our training experiences (good and bad), junior doctors are ideally placed to support more junior colleagues at all levels.

There is a need to develop links with other mentoring schemes to exchange experiences and learn lessons from others. Research has shown the importance of supporting mentors in their roles through regular meetings where mentors learn from each other. 13

In our experience, the mentoring scheme worked both alongside and separately to clinical and educational supervision and the opportunity for reflective practice offered in Balint groups. Mentoring added another level of support for the Foundation doctors, which was deemed beneficial by those participating.

We recommend more research is required to determine whether mentoring will increase recruitment to psychiatry. Organisations responsible for the training of doctors should support formal mentoring schemes and supervisors should ensure that mentors and mentees have protected time in their timetable due to the benefits of the mentoring experience to the doctors and the employing organisations.

Finally, funding should be available to support training of mentors in their workplace and aim to develop their skills in helping their mentees. Many private organisations offer mentoring training packages (including classroom and online training) for competitive prices. These courses provide useful resources to mentors and may help to increase the motivation of mentors to continue their participations in mentoring.

Appendix:

How does mentoring work? A simple three stage model:

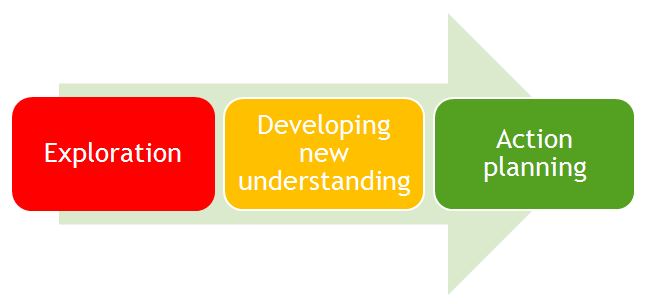

Figure 1- The three stage model of mentoring. Developed from Alred et al (1998). Alred, G., Gravey, B. and Smith, R, 1998, Mentoring pocketbook. Alresford: Management Pocketbooks.

One of the unique characteristics of mentoring is that it is a partnership between two individuals (mentor and mentee) where both contribute to its growth and sustainability. It is based on trust, eagerness to learn and mutual respect. 16

Alred et al (1998) 4 described a model of mentorship with three stages: exploration, developing new understanding and then action planning (Figure 1). Both the mentors and mentee have certain roles and responsibilities in each stage and it is only through their collaborative work that the benefits of mentoring can be obtained.

The stage of exploration is characterised by the building of a relationship between the mentor and the mentee. Trust, confidence and rapport start to develop and hopefully grow throughout the mentoring process. Methods such as active listening, asking open questions, and negotiating an agenda are essential to facilitate this growth.

The second stage is where new understanding develops, is characterised by showing support to the mentee, demonstrating skills in giving constructive feedback and challenging negative and unhelpful cognitions.

Key methods employed in this stage include recognition of the strengths and weaknesses of the mentee, giving them information, sharing experience and establishing priorities for the mentee to work on.

In the third and last stage of the mentoring, action planning, the mentee takes the lead in negotiating and agreeing on the action plan, examining their options and developing more independent thinking and decision-making abilities.

A good mentor should help the mentee to gain confidence and knowledge over time. In order to achieve this, the mentor helps the mentee to develop new ways of thinking and improve their problem-solving abilities.

Monitoring the progress and evaluating the outcomes of the mentoring process is essential to ensure that the mentoring relationship is going in the right direction.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr Stephen Jones (Consultant CAMHS and former Training Programme Director), Dr Trevor Broughton (Consultant Forensic Psychiatrist, Director of Medical Education), Dr Bohdan Solomka (Medical Director) from Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust for their unlimited support for the mentoring scheme.

We also would like to thank Dr Calum Ross (Foundation Training Programme Director-FY1) and Mr Am Rai (Foundation Training Programme Director -FY2), Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital for their support in implementing this scheme. Dr Srinaveen Abkari (Specialist Registrar, Norfolk, and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust) is one of our mentors who also contributed useful ideas to the development of this paper.

Finally, we would like to thanks all our mentors who provided the support for the Foundation, without their efforts, this scheme would not have succeeded.

|

Competing Interests None declared Author Details YASIR HAMEED MRCPsych, PgCert Clin Edu, FHEA, Honorary Lecturer Norwich Medical School, Specialist Registrar in Adult and Older Adult Psychiatry, Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust, Hellesdon Hospital, Norwich, UK. HUGO DE WAAL FRCPsych, MD, FHEA, Consultant Old Age Psychiatrist, Norfolk & Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust, Associate Postgraduate Dean, Health Education East of England, UK. EMMA BOSIER MBBS, Core Psychiatry Trainee, Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust, UK. JAMES MILLER BSc Hons MBChB MRCPsych, Specialist Registrar, Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust, UK. JANE STILL MRCPsych, Specialist Registrar Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust, UK. DAWN COLLINS MBBS, Core Psychiatry Trainee, Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust, UK. THOMAS BENNET MBBS, PGCE, BA HONS, Foundation Doctor, James Paget Hospital, Lowestoft Road, Gorleston, Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, UK. CLARA HAROULIS MBChB, BSc MCB, Foundation Doctor, James Paget Hospital, UK. JACOBUS HAMELIJNCK Arts, MRCPsych, Consultant Psychiatrist, Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust, UK. NIGEL GILL MBBS, Academic Clinical Fellow, Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust, UK. CORRESPONDENCE: YASIR HAMEED, Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust, Hellesdon Hospital, Norwich, NR6 5BE. Email: yasirmhm@yahoo.com |

References

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. Broadening the Foundation Programme Strategy 2016-2021. 2016. [cited 2017 March 27]. Available from: http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/FoundationProgramme_Strategy_Jan16_Council.pdf

- Health Education England Broadening the Foundation Programme: Recommendations and Implementation Guidance. HEE, 2014. [cited 2017 March 27]. Available from:https://www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/hospitals-primary-community-care/learning-be-safer/better-training-better-care-btbc/broadening-foundation-programme

- Goodyear H, Bindal N, Bindal T, Wall D. Foundation doctors' experience and views of mentoring. British Journal of Hospital Medicine 2013, 74: 682-686.

- Alred G, Garvey B, Smith R. Mentoring Pocketbook 1998. Alresford: Management Pocketbooks.

- Nash S, Scammell J. How to use coaching and action learning to support mentors in the workplace. Nursing Times 2010, 106: 20-23.

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. A Guide to Psychiatry in the Foundation Programme for Supervisors. 2015. [cited 2017 March 27]. Available from: http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/A%20Guide%20to%20Psychiatry%20in%20the%20Foundation%20Programme.pdf

- Steele R, & Beattie S. Development of Foundation year 1 Psychiatry posts: implications for practice. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 2013, 19: 410.

- Dake S B, Taylor J A. Do as I Do: The Importance of the Clinical Instructor as Role Model The Journal of ExtraCorporeal Technology. Volume 26, Number 3, September 1994.

- Standing Committee on Postgraduate Medical and Dental Education SCOPME. Supporting Doctors And Dentists At Work: An Enquiry Into Mentoring. 1998, n.p.: London.

- Cottrell D. But What Exactly Is Mentoring? Invited Commentary On…Mentoring Scheme for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Consultants in Scotland. Psychiatric Bulletin: Journal of Trends in Psychiatric Practice 2009, suppl 33: 47.

- Buddeberg-Fischer B, Herta K-D. Formal mentoring programmes for medical students and doctors – a review of the Medline literature. Medical Teacher 2006; 28: 248–57.

- Development & Learning in Organizations. How mentors make a growing impact "Wise, trusted advisors", 2004, 18: 29. [cited 2017 March 27]. Available from: https://eoeleadership.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/1402608960_hNgk_how_mentors_make_a_growing_impact.pdf

- Connor MP, Bynoe AG, Redfern N, Pokora J, Clarke J. Developing senior doctors as mentors: a form of continuing professional development. Report of an initiative to develop a network of senior doctors as mentors: 1994-99. Medical Education 2000, 34: 747-753.

- Mentoring – Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) Factsheet. Revised February 2009. [cited 2017 March 27]. Available from: https://www.shef.ac.uk/polopoly_fs/1.110468!/file/cipd_mentoring_factsheet.pdf

- Taherian K, Shekarchian M. Mentoring for doctors. Do its benefits outweigh its disadvantages? Medical Teacher 2008, 30: 95-99.

- McCarthy B, Murphy S. Assessing undergraduate nursing students in clinical practice: Do preceptors use assessment strategies? Nurse Education Today 2008, 28: 301-313.

The above article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.