Approach to spasticity in General practice

Ganesh Bavikatte and Tarek Gaber

Cite this article as: BJMP 2009: 2(3) 29-34

|

|

Abstract Spasticity is a physiological consequence of an injury to the nervous system. It is a complex problem which can cause profound disability, alone or in combination with the other features of an upper motor neuron syndrome and can give rise to significant difficulties in the process of rehabilitation. This can be associated with profound restriction to activity and participation due to pain, weakness, and contractures. The treatment of spasticity is fundamental in the management of neurological disabilities. Optimum management is dependent on an understanding of its underlying physiology, an awareness of its natural history, an appreciation of the impact on the patient and a comprehensive approach to minimising that impact. The aim of this article is to highlight the importance, basic approach and management options available to the general practitioner in such a complex condition. |

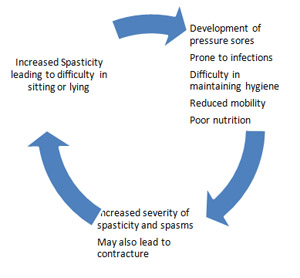

Spasticity is a common symptom seen as a consequence of an injury to the brain (stroke, trauma, hypoxia, infection, cerebral palsy and post surgery), spinal cord injury or multiple sclerosis. It is a complex problem, which can cause profound disability alone or in combination with other features of upper motor neuron syndromes (figure 1). The word “spasticity” is derived from the Greek word “spasticus”, which means “To pull or To Tug”. Spasticity is defined1 as “Disordered sensori-motor control, resulting from an upper motor neuron lesion, presenting as intermittent or sustained involuntary activation of muscles”. Simply stated, spasticity is stiffness of muscles that occurs after injury to the spinal cord or brain. Awareness of the implications and associated symptoms can minimise development of long term secondary complications (table 1). The impact of spasticity can be devastating. If not managed early and appropriately it may result in progressive disability, resulting in secondary complications such as contractures and pressure sores. This significant impact has ensured that spasticity management is a prominent feature in the national management guidelines for long term neurological conditions, promoting coordination of care between primary, secondary and social care providers. Symptoms Spasticity can range from mild muscle stiffness to severe, painful and uncontrollable muscle spasms. It is associated with both positive and negative components of upper motor neuron syndromes. Positive components include muscle overactivity, flexor and extensor spasm, hyperreflexia, athetosis, spastic dystonia, clonus, and an extensor plantar response. Common negative symptoms comprise weakness/ paralysis, early hypotonia, fatigue and loss of dexterity. Spasticity can be distinguished from rigidity by its dependence on the speed of muscle stretch and characteristic distribution in antigravity muscle groups. Spasticity does not always cause harm and can occasionally assist in the rehabilitation process by enabling a patient to stand when their limb weakness would not otherwise allow it Table 1 Clinical and functional problems associated with severe Spasticity

| Physical | Emotional / social |

| ·Non- specific pain·Discomfort·Painful muscle spasm·Difficulties with activities of daily living. e.g. washing, dressing, eating, toileting, maintaining hygiene, sexual activity·Problems with posture and mobility·Physical deformity and longterm contracture·Pressure ulcers | ·Emotional e.g. low mood, distorted self image, impaired motivation·Impact on fulfilment of life roles as a partner or a parent·Sleep disturbance – due to pain and discomfort·Vocational- impact on employment or education·Social isolation – due to restricted mobility |

Figure 1 Vicious cycle of spasticity  Assessment of spasticity Before any intervention is undertaken to modulate hypertonicity, it is important to attempt to assess the severity of spasticity. Many grading scales are used to quantify spasticity. These address the degree of muscle tone, the frequency of spontaneous spasms and the extent of hyperreflexia. Goniometry, Ashworth scale, Tardieu Scales, Goal attainment scale are only a few of these scales. One of the most widely used scales is the modified Ashworth scale2. Table 2 Modified Ashworth scale

Assessment of spasticity Before any intervention is undertaken to modulate hypertonicity, it is important to attempt to assess the severity of spasticity. Many grading scales are used to quantify spasticity. These address the degree of muscle tone, the frequency of spontaneous spasms and the extent of hyperreflexia. Goniometry, Ashworth scale, Tardieu Scales, Goal attainment scale are only a few of these scales. One of the most widely used scales is the modified Ashworth scale2. Table 2 Modified Ashworth scale

| 4 Rigid extremity 3 Loss of full joint movement, difficult movement, considerable tone2 Full joint/ limb movement, but more increase in tone, limb still easily moved.1+ Slight increase in tone, catch and resistance through out range of movement1 Slight increase in tone, catch or minimal resistance at end of range of movement0 no increase in tone |

It is also important to remember that not every “tight” muscle is spastic. The clinically detectable increase in muscle tone may be due to spasticity, rigidity or a fixed muscle contracture. Management The key to successful spasticity management is education of the patient and carers with both verbal and written information. This allows them to understand, appreciate and be fully involved in the management plan. All patients with spasticity should be followed up by a coordinated multidisciplinary team, which allows more timely intervention and close monitor of the progress. Liaison between health and social services in both primary and secondary care is essential in long term management. This helps to deliver a more consistent approach to the individual over time (figure 2). Table 3 Aims of spasticity management.

| 1.Improve function- mobility , dexterity2.Symptom relief-· Ease pain- muscle shortening, tendon pain, postural effects· Decrease spasms· Orthotic wearing3. Postural- Body image4. Decrease carer burden- Care and hygiene, positioning, dressing5. Optimise service responses- to avoid unnecessary treatments, facilitate other therapy, delay/prevent surgery |

The first step in the management of spasticity is to identify the key aims and realistic goals of therapy. Understanding the underlying pathology and possible prognosis is helpful in planning these goals (table 3). Other key points to consider are: · Identification and management of any trigger or aggravating factors-Initial assessment should exclude any co morbidity that may worsen spasticity such as pressure sores, chronic pain, infection (commonly urinary tract infection), constipation or in-growing toe nails.· Instigation of an effective and realistic physical programme including attention to posture and positioning Figure 2

Approach to spasticity assessmentComprehensive assessment of spasticityRecognition of underlying provocative factorsImpact on the individualMeasurement of spasticityPotential goals- individualised and person focussed

Initial approachEducation to patient/ and their family /carersMultidisciplinary team assessmentIdentification of clear treatment goalsEstablish mechanism for monitoring and review Management Manage triggering factorsBalance between positioning and movementPosture and seatingPhysical therapy and active exercise programmeSplinting and use of orthoticsPharmacotherapy A) Physical modalities· Stretching- this intervention has the benefit of being benign and non-invasive. Maintaining muscle length through passive or active exerciseand stretching regimens including standing or splinting canbe key to managing spasticity both in the short and the longterm.· Cooling of muscles- this inhibits mono synaptic stretch reflex and lowers the receptor’s sensitivity, different techniques such as quick icing and evaporating spray like ethyl chloride are occasionally used.· Heat-heat may increase the elasticity of the muscles. Techniques used include ultrasound, fluidotherapy, paraffin, superficial heat and whirlpools. These techniques should be combined with stretching and exercise.· Orthosis/equipment/ aids – an orthosis or splint is an external device designed to apply, distribute or remove forces to or from the body in a controlled manner to control body motions and /or alter the shape of body tissues. E.g. ankle foot orthosis, insoles, ankle supports, wrist/ hand/ elbow splints, knee splints, spinal brace, hip brace, neck collar. Some equipment can also aid positioning e.g. T roles, wedges, cushions and foot straps.These are usually used in combination with other modalities like botox therapy. Attention to posture and positioning, whichmay include the provision and regular review of seating systems,is paramount in managing severe spasticity· Massage– althoughvarious techniques are in use there is no evidence to support this· Dynamic physiotherapy technique- many schools of physiotherapy claim that particular technique has antispastic and functional benefits, particularly for the more mobile person. E.g. Bobath technique, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation, Brunnstrom technique. B) Electrical therapy· Functional Electrical stimulation –Thisis an adjunct to physiotherapythat can be of benefit to selected individuals who are predominantlyaffected by upper motor neuron pathologies resulting in a foot drop. Randomised controlled trial by Burridge et al in patients following stroke found that the use of functional electrical stimulation in combination with physiotherapy was statistically superior to physiotherapy alone3· Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation – this has been found to reduce spasticitythrough its nociceptive action and reduction of pain. C) PharmacologicalMedicationshould always be used as adjunct to good general management and education. Identification of treatment goals will help optimise drug therapy not only in terms of choice of agent, but also in timing and dose. Aims of medication should be to improve function or relieve troublesome symptoms rather than to simply reduce the degree of spasticity. Table 4 Useful things to remember to optimise medication effects

| 1. Clear written/verbal information for patients about effects/adverse symptoms of drugs 2. Clear treatment goals3. Detailed drug history- Review of other medication and potential drug interaction4. Appropriate form of drug e.g. liquid preparation if swallowing difficulties5. Regular review of efficacy and side effects6. Aids to help administer drugs e.g. dossette box, timer to remind7. “Start low and go slow” to avoid deleterious effects on function or unwanted side effects8. Combination of drugs to obtain synergistic action |

Table 5 Different methods of delivery of medication

| ·Enteral – orally or via PEG e.g. baclofen, benzodiazepins, dantrolene, clonidine, tizanidine, gabapentin·Transdermal system e.g. catapress TTS·Intrathecal e.g. baclofen pump (other drugs used alone or in combination intrathecally include clonidine, morphine, fentanyl, midazolam, lidocaine)·Intra muscular/ focal injection e.g. botulinum toxin·Nerve blocks e.g. Phenol, Ethanol |

The oral agentsAlthough different categories of drugs are available, those most commonly used to treat spasticity are baclofen,tizanidine, benzodiazepines, dantrolene, and gabapentin4, 5, 6. Different agents act through different mechanisms (table 6 and 7) for e.g. GABA-like (baclofen, benzodiazepine), central alpha 2 agonists (tizanidine, clonidine) and peripheral anti-spastics (dantrolene). Antispastic drugs act in the CNS either by suppression of excitation (glutamate), enhancement of inhibition (GABA, glycine) or a combination of the two. Table 6 Mechanism of action of commonly used oral antispasticity medication

| Drugs acting on | Drugs |

| GABA- ergic system | baclofen, benzodiazepines, piracetam, progabide |

| Ion flux | dantrolene sodium, lamotrigine, riluzole |

| Monoamines | tizanidine, clonidine, thymoxamine, beta blockers, and cyproheptadine |

| Excitatory amino acids | orphenadrine citrate, cannabinoids, inhibitory neuromediators and other miscellaneous agents. |

Baclofen remains the most commonly used anti-spastic agent. The preferential indication is spasticity caused by spinal cord disease especially in multiple sclerosis. Many studies including the pilot study by Scheinberg et al 7 demonstrated that oral baclofen has an effect beyond placebo in improving goal-oriented tasks (such as transfers), in children with spastic quadriplegic cerebral palsy. In open-label studies of oral baclofen, the drug improved spasticity in 70-87 per cent of patients; additionally improvement in spasms was reported in 75-96 per cent of patients. In double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled trials, baclofen was reported to be effective, producing statistically significant improvements in spasticity8. The main adverse effects of oral baclofen include sedation or somnolence, excessive weakness, vertigo and psychological disturbances. The incidence of adverse effects is reported to range from 10 to 75 per cent. The majority of adverse effects are not severe; most are dose related, transient and/or reversible. The main risks of oral baclofen administration are related to withdrawal; seizures, psychic symptoms and hyperthermia. These symptoms improve after the reintroduction of baclofen, usually without sequelae. When not related to withdrawal, these symptoms mainly present in patients with brain damage and in the elderly. The limited data on baclofen toxicity in patients with renal disease suggest that administration of the drug in these persons may carry an unnecessarily high risk. Tizanidine is an efficient and well tolerated antispastic. It is predominantlyan alpha 2 agonist and thus decreases presynaptic activity of theexcitatory interneurones. There is a large body of evidence for the effective use of tizanidine monotherapy in the management of spasticity 15. Tizanidine is the antispasticity drug that has been most widely compared with oral baclofen. Studies have generally found the two drugs to have equivalent efficacy, although tizanidine has better tolerability; in particular weakness was reported to occur less frequently with tizanidine than with baclofen.Dantrolene has a peripheral mechanism of action and acts primarily on muscle through inhibitingcalcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. It decreasesthe excitation–coupling reaction involved in muscle contraction and can be prescribed in the different forms of spasticity. The efficacy of benzodiazepines (diazepam, tetrazepam, clonazepam) is comparable with baclofen. Although there is no evidence to suggest any difference in effectiveness between them, diazepam and dantrolene are associated with more side effects than baclofen and tizanidine. There are other compounds with anti-spastic properties (gabapentine, cyproheptadine, piracetam). Their advantage is

Table 7

| Drug | Dosage | Doses per day | Mechanism of action | Common side effects | |

| Initial dosage | Maximum dosage | ||||

| Baclofen | 5mg x3 | 90mg | 4 | GABA ergic | Seizure, Sedation, Dizziness, GI disturbances, psychosis, Muscle weakness |

| Baclofen (intrathecal) | 25 micro | 500-1000 micro | infusion | Decreased ambulation speed,Muscle weakness | |

| Tizanidine | 2- 4 mg | 36mg | 2 to 3 | Agonist at alpha 2 adrenoreceptors | Liver dysfunction, Dry mouth |

| Diazepam | 5mg or 2mg x2 | 60mg | GABA agonist | Dizziness Somnolescence , muscle weakness Addiction | |

| Dantrolene | 25mg | 400mg | 4 | Inhibits release of intramuscular calcium stores | Hepatotoxicity, Decreased ambulation speed, Muscle weakness |

| Clonazepam | 0.5mg | 3mg | Sedation, Muscle weakness | ||

| Gabapentin | 100mg | 400mg x3 | GABA agonist | Sedation, Dizziness | |

rather limited when used alone. Generally, they are administrated in combination with usual anti-spastic drugs. A few short term trials have trialed gabapentin with good results 19 .Pregabalin may be of value as a systemic agent in the treatment of spasticity, although properly controlled studies with clearly defined outcome measures are required to confirm this finding 22. The Sativex Spasticity in MS Study Group23 concluded that oromucosal whole plant cannabis-based medicine (CBM) containing delta-9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) may represent a useful new agent for treatment of the symptomatic relief of spasticity in MS.

Intrathecal pump· Baclofen- If oral drug treatment is inadequate in controlling lower limb spasticity or is not tolerated, intrathecal delivery of baclofen should be considered. This has been found to be a cost-effective strategy when compared to conventional medical management alone by Bensmail et al 20 .The benefits of continuous intrathecal baclofen infusion have been demonstrated in more than 80 percent and over 65 percent of patients report an improvement in tone and spasms respectively. The main risks of intrathecal baclofen infusion are symptoms related to overdose or withdrawal. These are mostly related to catheter disruption, failure to refill the pump reservoir or failure of the pump's power source. Abrupt disruption of intrathecal baclofen can be a serious scenario with continuous spasms, tremors, temperature elevation, seizure and death having been reported.· Phenol- As phenol is a destructive agent which indiscriminately damagesmotor and sensory nerves, it is reserved for those individualswho do not have any functional movement in the legs, who havelost bladder and bowel function and who have impaired leg sensation. Intrathecal phenol can be an effective treatmentwhich, though it requires expert administration, does not havethe long term maintenance or cost issues that are associated with intrathecalbaclofen treatment. The effect of a single injection often lastsmany months and can be repeated if necessary 24. D) Nerve blockPeripheral nerve blockade/ Regional blocks/ Neurolytic blockade25 are another therapeutic possibility in the treatment of spasticity. This can be done with the help of fluoroscopy or nerve stimulation. Chemical neurolysis by phenol/ alcohol is irreversible and can be used at several sites. Blocks are applied most often to 4 peripheral sites: the pectoral nerve loop, median, obturator, and tibial nerves. The main indication is debilitating or painful spasticity. Peripheral blocks with local anaesthetics are used as tests to mimic the effects of motor blocks and determine their potential adverse effects. Peripheral neurolytic blocks are easy to perform, effective, and inexpensive30. E) Botulinum toxin injectionBotulinum toxin is the most widely used treatment for focal spasticity27,28,29. The effect of the toxin is to inhibit the release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction. The clinical effect of injecting botulinum toxin is reversible due to nerve sprouting and muscle reinnervation, leading to functional recovery of the muscle in a few months. It is essential that botulinum toxin injections are given in conjunction with physiotherapy in order to obtain the maximum benefit. The toxin is injected directly into the targeted muscle and an effect can be noticed from as early as 2-3 days with a maximum effect seen by about 3 weeks, lasting at least 3 months. As it is not a permanent treatment it may have to be repeated after a few months.Many randomisedcontrolled trials show that botulinum toxin is effectivein reducing muscle tone in various conditions 28, 29. Brashear and colleaguesdemonstrated a reduction in spasticity in the wrist andfingers of patients following stroke with the use of botulinum toxin, together with an improvementin their disability assessment scale29.E) Surgical techniqueMost surgical procedures are irreversible. This means that realistic goal setting between the health care provider, family and patient is critical. Neurosurgical techniques have been proven useful in conditions like cerebral palsy 32, 33.· Neurosurgical techniques- Anterior and posterior rhizotomy, peripheral neurotomy 31, Drezotomy, percutaneous radiofrequency rhizotomy, spinal cord and deep cerebellar stimulation of the superior cerebellar peduncle 32, functional neurosurgery 33· Orthopaedic procedures- directly act on muscles and tendons e.g. lengthening operation, tenotomy, neurectomies, and transfer of tendons.

| Key Points to remember1.Spasticity management is more effective in multidisciplinary settings2.Early multidisciplinary approach and goal setting is crucial3.Education and clear communication between patients, carers and health care providers is essential4.Early intervention and optimal therapy prevents long term complications.5.Focal spasticity responds well to botulinum toxin injection, while generalised spasticity needs oral/ intrathecal medications |

|

Author Details <p>GANESH BAVIKATTE MBBS, MD, MRCP, Speciality Trainee Registrar Rehabilitation Medicine, North West Deanery. 12 Gambelside close Ellenbrook, Worsley, Manchester M28 7XU.</p> <p>Dr TAREK A-Z K GABER, MB BCh, MSc, MRCP (UK) Consultant in Neurological Rehabilitation Leigh Infirmary, Greater Manchester Neuro-rehabilitation Network, UK.</p> CORRESPONDENCE: GANESH BAVIKATTE MBBS, MD, MRCP, Speciality Trainee Registrar Rehabilitation Medicine, North West Deanery. 12 Gambelside close Ellenbrook, Worsley, Manchester M28 7XU Email: ganeshbhat357@doctors.net.uk |

References

1. Pandyan AD, Gregoric M, Barnes MP, Wood D, Van Wijck F, Burridge J, Hermens H, Johnson GR, Spasticity: clinical perception, neurological realities and meaningful measurement. . Disability and Rehabilitation 2005; 27(1/2):2-6

2. Bohannnon, R.W and Smith M.B, Modified Ashworth scale, (1986). Physical therapy 67, 206-7

3. Burridge J, Taylor P, Hagan S, The effects of common peroneal stimulation on the effort and speed of walking: a randomised controlled clinical trial with chronic hemiplegic patients. Clin Rehabil 1997;11:201–10

4. Campistol J. Orally administered drugs in the treatment of spasticity Rev Neurol. 2003 Jul 1-15;37(1):70-4

5. Rode G, Maupas E, Luaute J, Courtois-Jacquin S, Boisson D Medical treatment of spasticity, Neurochirurgie. 2003 May;49(2-3 Pt 2):247-55

6. Taricco M, Pagliacci MC, Telaro E, Adone R.Pharmacological interventions for spasticity following spinal cord injury: results of a Cochrane systematic review. Eura Medicophys. 2006 Mar;42(1):5-15

7. Scheinberg A, Hall K, Lam LT, O'Flaherty S. Baclofen in children with cerebral palsy: a double-blind cross-over pilot study. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006 Nov;42(11):715-20

8. Dario A, Tomei G A benefit-risk assessment of baclofen in severe spinal spasticity. Drug Saf. 2004;27(11):799-818

9. Suheda Ozcakir, MD and Koncuy Sivrioglu, MD Botulinum Toxin in Poststroke Spasticity; Clin Med Res. 2007 June; 5(2): 132–138.

10. Lance J W Spasticity: disordered motor control, 1980. pp 185-204

11. Joel A DeLisa, Bruce M. Gans, Nicholas E. Walsh, William L. Bockenek, Text book of physical medicine and rehabilitation: principles and practice.2006, page1426-30

12. Spasticity in adults: Management using botulinum toxin, National Guidelines, Royal college of Physicians, Jan 2009

13. Dr Peter Moore and Markus Naumann, Handbook of Botulinum Toxin treatment 2nd edition, 2003.

14. Tarek A.-Z.K.Gaber Case studies in neurological rehabilitation, Cambridge university press, 2008.

15. Valerie L. Stevenson, Alan J. Thompson, Louise Jarrett, Text book of Spasticity Management A practical multidisciplinary guide 2006.

16. Michael P.Barnes and Anthony B.Ward, Oxford Handbook of Rehabilitation Medicine, Oxford University Press, 2005, p 85-104.

17. Anthony B Ward, Handbook of the management of adult spasticity course, Stoke on Trent, 2008.

18. A J Thompson, L Jarrett, L Lockley, J Marsden and V L Stevenson, Clinical management of spasticity, JNNP(journal of neurology, neurosurgery and psychiatry) 2005;76:459-463

19. Beard S, Hunn A, Wright J. Treatments for spasticity and pain in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess 2003;7:1–111

20. Bensmail D, Ward AB, Wissel J, Motta F, Saltuari L, Lissens J, Cros S, Beresniak A. Cost-effectiveness Modeling of Intrathecal Baclofen Therapy versus Other Interventions for Disabling Spasticity Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009 Jul; 23(6):546-52. Epub 2009 Feb 19

21. Kamen L, Henney HR 3rd, Runyan JD. A practical overview of tizanidine use for spasticity secondary to multiple sclerosis, stroke, and spinal cord injury. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008 Feb;24(2):425-39

22. Bradley LJ, Kirker SG. Pregabalin in the treatment of spasticity: a retrospective case series. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30(16):1230-2

23. Collin C, Davies P, Mutiboko IK, Ratcliffe S; Sativex Spasticity in MS Study Group. Randomized controlled trial of cannabis-based medicine in spasticity caused by multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2007 Mar;14(3):290-6

24. Jarrett L, Nandi P, Thompson AJ. Managing severe lower limb spasticity in multiple sclerosis: does intrathecal phenol have a role? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;73:705

25. Viel EJ, Perennou D, Ripart J, Pélissier J, Eledjam JJNeurolytic blockade of the obturator nerve for intractable spasticity of adductor thigh muscles. Eur J Pain. 2002;6(2):97-104

26. Richardson D, Sheean G, Werring D et al, Evaluating the role of botulinum toxin in the management of focal hypertonia in adults, J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;69:499–506

27. Wissel J, Entner T.Botulinum toxin treatment of hip adductor spasticity in multiple sclerosis Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2001;113 Suppl 4:20-4

28. Brashear A, Gordon MF, Elovic E, Botox Post-Stroke Spasticity Study Group. Intramuscular injection of botulinum toxin for the treatment of wrist and finger spasticity after a stroke. N Engl J Med 2002;347:395–400

29. Rosales RL, Chua-Yap AS.Evidence-based systematic review on the efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin-A therapy in post-stroke spasticity. 2008; 115(4):617-23. J neural transmits. Epub 2008 Mar 6.

30. Viel E, Pellas F, Ripart J, Pélissier J, Eledjam JJ. Peripheral nerve blocks and spasticity. Why and how should we use regional blocks?] Presse Med. 2008 Dec; 37(12):1793-801. Epub 2008 Sep 4.

31. Maarrawi J, Mertens P, Luaute J, Vial C, Chardonnet N, Cosson M, Sindou M.Long-term functional results of selective peripheral neurotomy for the treatment of spastic upper limb: prospective study in 31 patients. J Neurosurg. 2006 Feb;104(2):215-25

32. Harat M, Radziszewski K, Rudaś M, Okoń M, Galanda M. Clinical evaluation of deep cerebellar stimulation for spasticity in patients with cerebral palsy. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2009 Jan-Feb;43(1):36-44

33. Siegfried J, Lazorthes Y, Broggi G, Claverie P, Deonna T, Frerebeau P, Verdie JC, Alexandre F, Angelini L, Benezech J. Functional neurosurgery of cerebral palsy Neurochirurgie. 1985;31 Suppl 1:1-118

The above article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.