John Ellis Agens

Abstract

A restraint is a device or medication that is used to restrict a patient’s voluntary movement. Reported prevalence of physical restraint varies from 7.4% to 17% use in acute care hospitals up to 37% in long term care in the United States. Prevalence of 34% psychotropic drug use in long term care facilities in the United States has been reported; but use is decreasing, probably due to regulation. Use of restraints often has an effect opposite of the intended purpose, which is to protect the patient. The risk of using a restraint must be weighed against the risk of not using one, and informed consent with proxy decision makers should occur. Comprehensive nursing assessment of problem behaviours, a physician order when instituting restraints, and documentation of failure of alternatives to restraint is required. Ignorance about the dangers of restraint use results in a sincere, but misguided, belief that one is acting in the patient’s best interest.Steps can be taken to reduce restraints before the need for restraints arises, when the need for restraints finally does arise, and while the use of restraints is ongoing.

Keywords: physical restraint, chemical restraint, aged care, antipsychotic agents, therapeutic use, psychotropic agents, treatment outcome, regulations

|

Definition of restraint: a device or medication that is used to restrict a patient’s voluntary movement.

Prevalence of physical restraints: up to 17% in acute care settings.

Prevalence of chemical restraints: up to 34% psychotropic drug use in long term care facilities.

Complications of restraints: include documented falls, decubitus ulcers, fractures, and death.

Regulations: require documentation of indications plus failure of alternatives by a licensed professional.

Prevention of removal of life sustaining treatment: is a relatively clear indication for restraints.

Informed consent: including consideration of risks, benefits, and alternatives is necessary in all cases.

Barrier to reducing restraints: a misguided belief that, by use, one is preventing patient injury.

Steps can be taken to limit their use: including an analysis of behaviours precipitating their use. |

Case study

A 79 year old female nursing home resident with frontotemporal dementia and spinal stenosis has a chronic indwelling catheter for cauda equina syndrome and neurogenic bladder. Attempts to remove the catheter and begin straight catheterization every shift were met by the patient becoming combative with the staff. Replacing the catheter led to repeated episodes of the patient pulling out the catheter. The patient lacks decision making capacity to weigh the risks, benefits, and alternatives; but she clearly doesn’t like having a catheter in. The attending physician instituted wrist restraints pending a team meeting. Unfortunately, attempts by the patient to get free led to dislocation of both shoulders and discharge to the hospital.

Introduction

A restraint is any device or medication used to restrict a patient’s movement. In the intensive care unit, for example, soft wrist restraints may be used to prevent a patient from removing a precisely placed endotracheal tube. A lap belt intended to prevent an individual from falling from a wheelchair in a nursing home is a restraint if the patient is unable to readily undo the latch.1 In the case study above of a catheterized, demented patient, if medication is used to prevent the patient from striking out at staff when performing or maintaining catheterization, then the medication is considered a restraint.

There is little data on efficacy and benefits of restraints1. Even when the indication to use a restraint is relatively clear, the outcome is often opposite of the intention. Consider that restraints used for keeping patients from pulling out their endotracheal tubes are themselves associated with unplanned self- extubation2. Complications of restraints can be serious including death resulting from medications or devices3,4. Use of restraints should be reserved for documented indications, should be time limited, and there should be frequent re-evaluation of their indications, effectiveness, and side effects in each patient. Lack of a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved indication for use of medications as restraints in agitated, aggressive, demented patients has led to recommendations that medications in these situations be used only after informed consent with proxy decision makers5. Medical, environmental, and patient specific factors can be root causes of potentially injurious behavior to self or others as in the case study above. To ensure consideration and possible amelioration of these underlying causes, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS ) in 2006 required face to face medical and behavioral evaluation of a patient within one hour after restraints are instituted by a physician (licensed independent practitioner). As a result of controversy surrounding this rule, clarification of that rule in 2007 allowed for a registered nurse or physician assistant to perform the evaluation provided that the physician is notified as soon as possible6 . In depth situational analysis of the circumstances surrounding the use of restraints in individual cases as well as education of the patient, family, and caregivers may lead to the use of less restrictive alternatives7.

Frequency of restraint use

Frequency of restraint use depends on the setting, the type of restraint, and the country where restraint use is being studied. In the acute care hospital setting, reported physical restraint use was 7.4% to 17%.a decade ago8.Two decades ago, in long term care facilities prevalence was reported as 28%-37%.9 . There has been a steady decline over the past several decades coincident with regulation such that, according to the Department of Health and Human Services, it is down to about 5% since newer CMS rules went into effect in 2007. In contrast, some European nursing homes still report physical restraint use from 26% to 56%10,11.

Chemical restraint is slightly more prevalent than physical restraint with a prevalence of up to 34% in long term care facilities in the US prior to regulations12.There is some indication that prevalence may be decreasing, some say markedly, perhaps as a result of government regulation13,12 .Interestingly, one case-control study of more than 71,000 nursing home patients in four states showed that patients in Alzheimer special care units were no less likely to be physically restrained compared to traditional units. Furthermore, they were more likely to receive psychotropic medication14.

Complications of restraint use

The use of chemical and physical restraints is associated with an increase in confusion, falls, decubitus ulcers, and length of stay15,16. Increase in ADL dependence, walking dependence, and reduced cognitive function from baseline has also been reported17. Use of restraints often has an effect opposite the intended purpose of protecting the patient, especially when the intent is prevention of falls18. Physical restraints have even caused patient deaths. These deaths are typically due to asphyxia when a patient, attempting to become free of the restraint, becomes caught in a position that restricts breathing4,19.

Antipsychotic medications may be used as restraints in elderly patients with delirium or dementia who become combative and endanger themselves and others; however, there is no FDA approval for these drugs for this use5. In a meta-analysis, an increased relative risk of mortality of 1.6 to 1.7 in the elderly prompted the FDA to mandate a “black box” label on atypical antipsychotic medications stating that they are not approved for use in the behavioral manifestations of dementia20. Other research suggests that conventional antipsychotics are just as likely to cause death, if not more so3. Forensic research also links antipsychotic medication and patient deaths21. The reported relative risk of falls from these drugs is 1.722. Given the risks, if antipsychotic medications are used at all, they need to be prescribed as part of a documented informed-consent process. Education of patients, families of patients, and facility staff about the harms of restraints is a good first step in a plan to avoid or eliminate their use. Over the past several decades, regulations have arisen in the United States because of complications of restraints and a lack of clear evidence supporting their use.

The regulatory environment in the United States

The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 (OBRA 87) resulted in regulations that specify the resident’s right to be free of the use of restraints in nursing homes when used for the purpose of discipline or convenience and when not required to treat the resident’s medical symptoms23,24. OBRA87 related regulations also specified that uncooperativeness, restlessness, wandering, or unsociability were not sufficient reasons to justify the use of antipsychotic medications. If delirium or dementia with psychotic features were to be used as indications, then the nature and frequency of the behavior that endangered the resident themselves, endangered others, or interfered with the staff’s ability to provide care would need to be clearly documented24. Comprehensive nursing assessment of problem behaviors, a physician order before or immediately after instituting a restraint, and documentation of the failure of alternatives to restraint are required before the use of a restraint is permitted. The restraint must be used for a specific purpose and for a specified time, after which reevaluation is necessary.

The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) instituted similar guidelines that apply to any hospital or rehabilitation facility location where a restraint is used for physical restriction for behavioral reasons25. In response to the 1999 Institute of Medicine report, To Err is Human, JCAHO focused on improving reporting of sentinel events to increase awareness of serious medical errors. Not all sentinel events are medical errors, but they imply risk for errors as noted in the revised 2007 JCAHO sentinel event definition: A sentinel event is an unexpected occurrence involving death or serious physical or psychological injury, or the risk thereof6. The JCAHO recommends risk reduction strategies that include eliminating the use of inappropriate or unsafe restraints. The recommendations for restraint reduction are prioritized along with items like eliminating wrong site surgery, reducing post-operative complications, and reducing the risk of intravenous infusion pump errors6. It is clear that JCAHO considers placing restraints as a sentinel event to be monitored and reported. CMS and JCAHO have worked to align hospital and nursing home quality assurance efforts especially with respect to the standard concerning face to face evaluation of a patient within one hour of the institution of restraints. They held ongoing discussions that resulted in revised standards for the use of restraints in 200926. Among the agreed upon standards are: policies and procedures for safe techniques for restraint, face to face evaluation by a physician or other authorized licensed independent practitioner within one hour of the institution of the restraint, written modification of the patient’s care plan, no standing orders or prn use of restraints, use of restraints only when less restrictive interventions are ineffective, use of the least restrictive restraint that protects the safety of the patient, renewal of the order for a time period not to exceed four hours for an adult, restraint free periods, physician or licensed independent practitioner daily evaluation of the patient before re-ordering restraint, continuous monitoring, and documentation of strategies to identify environmental or patient specific triggers of the target behavior. The one hour face to face evaluation may be accomplished by a registered nurse provided that the attending physician is notified as soon as possible26.

Indications for use of restraints

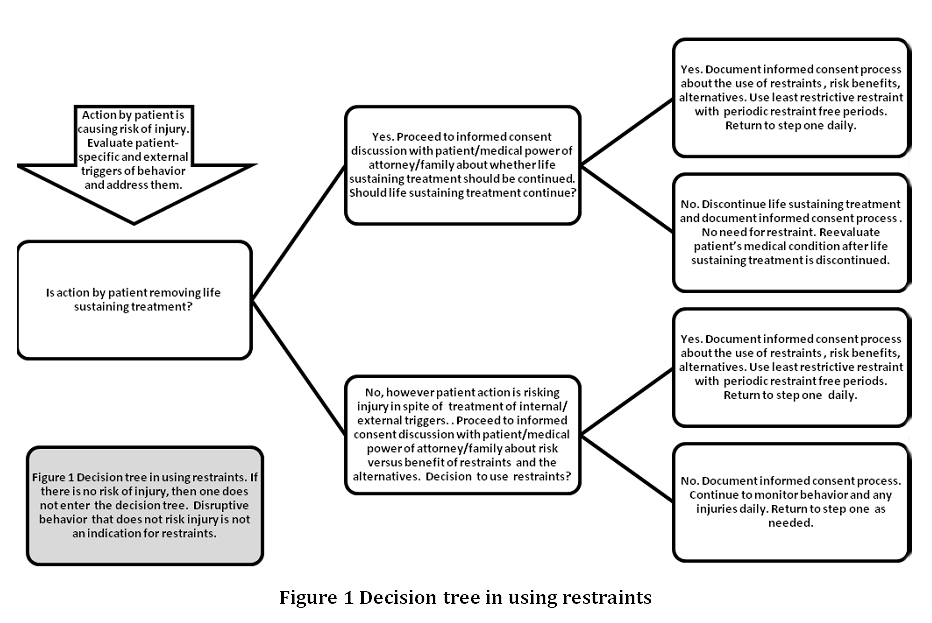

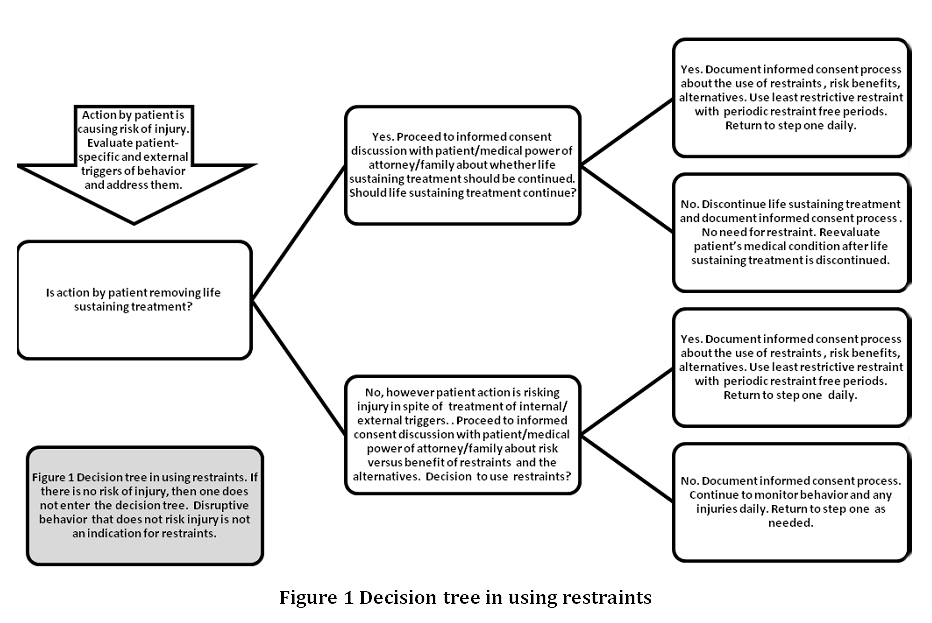

The risk of using a restraint must be weighed against the risk of not using one when physical restriction of activity is necessary to continue life-sustaining treatments such as mechanical ventilation, artificial feeding, or fluid resuscitation. Every attempt should be made to allow earlier weaning from these treatments, thereby rendering the restraint unnecessary. Even in cases where the indication is relatively clear, the risks, benefits, and alternatives must be weighed (see Figure).

In an emergency, when it is necessary to get a licensed provider’s order for a restraint to prevent a patient from disrupting lifesaving therapy or to keep a patient from injuring others, an analysis of what may be precipitating the episode is essential. Are environmental factors such as noise or lighting triggering the behavio? Are patient factors such as pain, constipation, dysuria, or poor vision or hearing triggering the disruptive behavior? Is there an acute medical illness? Is polypharmacy contributing? Psychotropic drugs and drugs with anticholinergic activity are common culprits. Patient, staff, family, and other health care providers need to be queried.

One must guard against perceiving the continued need for life-sustaining treatment and the use of restraints as being independent factors, because that misconception can lead to a vicious cycle. For example, a patient who has persistent delirium from polypharmacy and needs artificial nutrition and hydration which perpetuates the need for continued chemical and physical restraints. Correcting the polypharmacy and the restraint as a potential cause of the delirium can break the cycle. When restraints are indicated, one must use the least-restrictive restraint to accomplish what is needed for the shortest period of time. Restraint-free periods and periodic reassessments are absolutely required.

A weaker indication is the use of restraints to prevent patient self-injury when the danger is not imminent. Such an indication exists when a patient repeatedly attempts unsafe ambulation without assistance or when he or she cannot safely ambulate early in the process of rehabilitation from deconditioning or after surgery. In these cases, weighing the risks and benefits of the restraint is more difficult than when considering restraints to maintain life-sustaining treatment.

Even more difficult to justify is the use of restraints to restrict movement to provide nonurgent care. An example might be a patient who repeatedly removes an occlusive dressing for an early decubitus ulcer. In these cases, it is more fruitful to use alternatives to restraints. For example, considering alternatives to a urinary catheter is more important than documenting that restraints are indicated to keep the patient from pulling it out.

If used, the specific indication, time limit, and plan for ongoing reevaluation of the restraint must be clearly documented. Effectiveness and adverse effects must be monitored. Restraint-free periods are also mandatory. The same is true for chemical restraints. Periodic trials of dosage reduction and outcome are mandatory.

Barriers to reducing the use of restraints

Perceived barriers to reducing restraints can be thought of as opportunities to build relationships between patients, physicians, staff, patients’ families, and facility leaders. A legitimate fear of patient injury, especially when the patient is unable to make his or her own decisions, is usually the root motivation to use restraints. Ignorance about the dangers of restraint use results in a sincere, but misguided, belief that one is acting in the patient’s best interest27. Attempts to educate physicians, patients, and staff may not have been made. These barriers are opportunities for the community to work together in creative partnerships to solve these problems. Even in communities where there are no educational institutions, there are opportunities for educational leadership among physician, nursing, and other staff. Conversely, lack of commitment to reducing restraints by institutional leaders will tend to reinforce the preexisting barriers. Regulatory intervention has been a key part of gaining the commitment of institutional leadership when other opportunities were not seized. On the other hand, competing regulatory priorities such as viewing a serious fall injury as a ‘never event’ and simultaneously viewing institution of a restraint as a sentinel event may lead to reduced mobility of the patient18. An example of this would be the use of a lap belt with a patient-triggered release. The patient may technically be able to release the belt, but the restricted mobility may lead to deconditioning and an even higher fall risk when the patient leaves the hospital. In the process of preventing the serious fall injury or ‘never event’ there is, even at the regulatory level, intervention that may not be in the patient’s best interest. These good intentions are, again, a barrier to the reduction of the use of restraints and an opportunity for physician leadership in systems based care collaboration. Physician leadership probably needs to extend beyond educational efforts. Evidence suggests education may be necessary but not sufficient to reduce the use of restraints10.

Reducing the use of restraints

Steps can be taken to reduce the use of restraints before the need for them arises, when the need for restraints finally does arise, and while their use is ongoing.

Programs to prevent delirium, falls in high-risk patients, and polypharmacy are all examples of interventions that may prevent the need for restraints in the first place. Attention to adequate pain control, bowel function, bladder function, sleep, noise reduction, and lighting may all contribute to a restraint-free facility.

When a restraint is deemed necessary, a sentinel event has occurred. Attempts to troubleshoot the precipitating factors must follow. Acute illness such as infection, cardiac, or respiratory illness must be considered when a patient begins to demonstrate falls or begins to remove life-sustaining equipment. Highly individualized assessment of the patient often requires input from physical therapy, occupational therapy, social work, nursing, pharmacy, and family. If root causes are determined and corrected, the need for restraints can be ameliorated and alternatives can be instituted.

The least restrictive alternative should be implemented when needed. For example, a lowered bed height with padding on the floor can be used for a patient who is at risk for falls out of bed in contrast to the use of bedrails for that purpose. Another example is the use of a lap belt with a Velcro release as opposed to a vest restraint without a release. A third example is the use of a deck of cards or a lump of modeling clay to keep the patient involved in an alternative activity to the target behavior that may be endangering the patient or staff. Alternatives to the use of restraints need to be considered both when restraint use is initiated and during their use. Judicious use of sitters has been shown to reduce falls and the use of restraints28. When danger to self or others from patient behaviors and restraints are deemed necessary, a tiered approach has been recommended by Antonelli29 beginning with markers and paper or a deck of cards for distraction and then proceeding up to hand mitts, lap belts, or chair alarms if needed. Vest or limb restraints are the default only when other methods have been ineffective29.

Literature from the mental health field provides some guidance to those attempting to use the least intrusive interventions for older patient behaviors that endanger themselves or others. A combination of system-wide intervention, plus targeted training in crisis management to reduce the use of restraints has been demonstrated to be effective in multiple studies30. In a recent randomized controlled study, one explanation the author gives for the ineffectiveness the educational intervention is that the intervention was “at the ward level unlike other restraint reduction programs involving entire organizations.”10. Research and clinical care in restraint reduction will likely need to be both patient-centered and systems-based in the future.

Case study revisited

Our 79 year old female with frontotemporal dementia and spinal stenosis noted in the above case pulls out her urinary catheter. The physician is called and determines that the patient’s urine has been clear prior to the episode, that she has no fever, nor does she have evidence of acute illness. The patient is likely pulling the catheter out simply because of the discomfort caused by the catheter itself since the patients behavior is at the same baseline as before the catheter was inserted as determined by discussion with the staff. The patient is unable to inhibit her behavior because of the frontotemporal dementia. The physician places a call to the medical power of attorney and explains the risks of bladder infection, bladder discomfort, renal insufficiency, and overflow incontinence from untreated neurogenic bladder. This is weighed against the risk of frequent infections and bladder discomfort from a chronic indwelling urinary catheter, or damage to the urethra from pulling the catheter out. The option of periodic straight catheterization is dismissed by the medical power of attorney as being too traumatic for this demented patient who becomes agitated during this procedure.

The medical power of attorney considers the options and agrees to observation by the staff without the catheter overnight with a team conference the next day. At the conference, it was noted that overnight the patient had several episodes of overflow incontinence in spite being toileted every few hours while awake. The patient had no signs of discomfort and was changed when found to be wet. A bladder scan done at the facility showed a few hundred cubic centimeters of residual urine after the patient was noted wet and changed. The team conference yielded the informed decision to continue checking the patient frequently and changing when wet as well as frequent toileting opportunities.

The patient continued at baseline for twelve weeks until she developed urinary sepsis and the patient’s medical power of attorney was contacted about additional care decisions.

Conclusion

A restraint is any device or medication used to restrict a patient’s movement. Complications of restraints can be serious including death resulting from both medications and devices. Use of restraints should be reserved for documented indications, should be time limited, and there should be frequent re-evaluation of their indications, effectiveness, and side effects in each patient. Analysis of environmental and patient specific root causes of potentially self-injurious behavior can lead to reduction in the use of restraints. Education of the patients, families, and the health care team can increase the use of less restrictive alternatives.

Competing Interests

None declared

Author Details

John Ellis Agens Jr. MD FACP, Associate Professor of Geriatrics at Florida State University College of Medicine, 1115 W. Call Street, Suite 3140-H, Tallahassee, Florida 32306-4300

CORRESPONDENCE: John Ellis Agens Jr. Associate Professor of Geriatrics at Florida State University College of Medicine, 1115 W. Call Street, Suite 3140-H, Tallahassee, Florida 32306-4300

Email: john.agens@med.fsu.edu |

References

1. Chaves ES, Cooper RA, Collins DM, Karmarkar A, Cooper R. Review of the use of physical restraints and lap belts with wheelchair users. Assist Technol. Summer 2007;19(2):94-107.

2. Chang LY, Wang KW, Chao YF. Influence of physical restraint on unplanned extubation of adult intensive care patients: a case-control study. Am J Crit Care. Sep 2008;17(5):408-415; quiz 416.

3. Wang PS, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, et al. Risk of death in elderly users of conventional vs. atypical antipsychotic medications. N Engl J Med. Dec 1 2005;353(22):2335-2341.

4. Byard RW, Wick R, Gilbert JD. Conditions and circumstances predisposing to death from positional asphyxia in adults. J Forensic Leg Med. Oct 2008;15(7):415-419.

5. Salzman C, Jeste DV, Meyer RE, et al. Elderly patients with dementia-related symptoms of severe agitation and aggression: consensus statement on treatment options, clinical trials methodology, and policy. J Clin Psychiatry. Jun 2008;69(6):889-898.

6. JCAHO-Sentinelevents and Alerts. http://www.premierinc.com/safety/topics/patient_safety/links.jsp. Accessed August 13, 2009.

7. Koch S. Case study approach to removing physical restraint. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2001(7):156-161.

8. Kow JV, Hogan DB. Use of physical and chemical restraints in medical teaching units. CMAJ. Feb 8 2000;162(3):339-340.

9. Hawes C, Mor V, Phillips CD, et al. The OBRA-87 nursing home regulations and implementation of the Resident Assessment Instrument: effects on process quality. J Am Geriatr Soc. Aug 1997;45(8):977-985.

10. Huizing AR, Hamers JP, Gulpers MJ, Berger MP. A cluster-randomized trial of an educational intervention to reduce the use of physical restraints with psychogeriatric nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. Jul 2009;57(7):1139-1148.

11. de Veer AJ, Francke AL, Buijse R, Friele RD. The Use of Physical Restraints in Home Care in the Netherlands. J Am Geriatr Soc. Aug 13 2009.

12. Hughes CM, Lapane KL. Administrative initiatives for reducing inappropriate prescribing of psychotropic drugs in nursing homes: how successful have they been? Drugs Aging. 2005;22(4):339-351.

13. Snowden M, Roy-Byrne P. Mental illness and nursing home reform: OBRA-87 ten years later. Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act. Psychiatr Serv. Feb 1998;49(2):229-233.

14. Phillips CD, Spry KM, Sloane PD, Hawes C. Use of physical restraints and psychotropic medications in Alzheimer special care units in nursing homes. Am J Public Health. Jan 2000;90(1):92-96.

15. Evans D, Wood J, Lambert L. Patient injury and physical restraint devices: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. Feb 2003;41(3):274-282.

16. Frank C, Hodgetts G, Puxty J. Safety and efficacy of physical restraints for the elderly. Review of the evidence. Can Fam Physician. Dec 1996;42:2402-2409.

17. Engberg J, Castle NG, McCaffrey D. Physical restraint initiation in nursing homes and subsequent resident health. Gerontologist. Aug 2008;48(4):442-452.

18. Inouye SK, Brown CJ, Tinetti ME. Medicare nonpayment, hospital falls, and unintended consequences. N Engl J Med. Jun 4 2009;360(23):2390-2393.

19. Karger B, Fracasso T, Pfeiffer H. Fatalities related to medical restraint devices-asphyxia is a common finding. Forensic Sci Int. Jul 4 2008;178(2-3):178-184.

20. Friedman JH. Atypical antipsychotics in the elderly with Parkinson disease and the "black box" warning. Neurology. Aug 22 2006;67(4):564-566.

21. Jusic N, Lader M. Post-mortem antipsychotic drug concentrations and unexplained deaths. Br J Psychiatry. Dec 1994;165(6):787-791.

22. Guideline for the prevention of falls in older persons. American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society, and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Panel on Falls Prevention. J Am Geriatr Soc. May 2001;49(5):664-672.

23. Elon RD. Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 and its implications for the medical director. Clin Geriatr Med. Aug 1995;11(3):419-432.

24. Elon R, Pawlson LG. The impact of OBRA on medical practice within nursing facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. Sep 1992;40(9):958-963.

25. American Geriatrics Society. AGS position statement: restraint use. 2008; www.americangeriatrics.org/products/positionpapers/restraintsupdate.shtml. Accessed July 17, 2009.

26. "The Joint Commission issues revised 2009 accreditation requirements." Hospital Peer Review. . 2009.

27. Moore K, Haralambous B. Barriers to reducing the use of restraints in residential elder care facilities. J Adv Nurs. Jun 2007;58(6):532-540.

28. Tzeng HM, Yin CY, Grunawalt J. Effective assessment of use of sitters by nurses in inpatient care settings. J Adv Nurs. Oct 2008;64(2):176-183.

29. Antonelli MT. Restraint management: moving from outcome to process. J Nurs Care Qual. Jul-Sep 2008;23(3):227-232.

30. Paterson B. Developing a perspective on restraint and the least intrusive intervention. Br J Nurs. Dec 14-2007 Jan 10 2006;15(22):1235-124

The above article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.